In 1960, almost no one in business had the toolkit for thinking about corporate and business unit strategy that an above-average MBA student has under her belt today. BCG’s experience curves, Porter’s five forces, Bartlett and Ghoshal’s core competencies and other similar frameworks provided actionable ways of seeing aspects of business that we’d now feel blind without. Strategy applied to systems change is today where business strategy was sixty years ago: equally nascent as a field and equally full of potential.

In order to advance in applying strategy to systems change, we’ll need to unlearn much of what business strategy has taught us. Traditional strategy puts the institution in the foreground and asks how the institution can create and realize the most value. For a business, value might be denominated in financial terms. For non-profit institutions, value is denominated in some other currency of mission achievement. Bain’s formulation of strategy as “a proprietary set of actions that serve customers better than competition” and “the ‘science’ of allocating scarce resources” reflects this focus on the institution. What can we do better than others? How can we realize greatest value? How do we allocate our resources to achieve highest financial or social return?

Strategy in service of systems change takes the opposite view, placing a large outcome in the world in the foreground. Achieving this outcome will require an interlocking system of actors, but the institutional context one starts from functions simply as an instrument in this pursuit. Of course, strategy is always formulated from somewhere, whether by an organization or by a coalition of actors. For example:

- The Service Year Alliance “making a year of service a common expectation and opportunity for all young Americans as a way to tackle important challenges while transforming their own lives”

- Solutions Journalism Network “spreading the practice of solutions journalism… [rebalancing] the news, so that every day people are exposed to stories that help them understand problems and challenges, and stories that show potential ways to respond”

- The Rockefeller Foundation’s US Youth Employment team, committed to creating new opportunities for ‘opportunity youth’, a vulnerable segment of young people who are disconnected from both school and work

But while Service Year Alliance, Solutions Journalism Network and a US Youth Employment team at The Rockefeller Foundation can frame questions of strategy – just as a corporation like Procter & Gamble or an operating non-profit like Habitat for Humanity can – the focus isn’t on their competitive advantage. Rather, strategy begins by asking what will cause the relevant system in the world – e.g., the talent market for young Americans, the field of journalism, the talent practices of large employers that support better employment and prosperity outcomes for opportunity youth – to evolve in the desired way. This doesn’t mean that questions of competitive advantage, resource allocation and so on are irrelevant. Solutions Journalism Network can’t be an effective catalyst if they run out of money and their staff disbands. They can’t raise money without being perceived by donors as having an advantage in solving a problem the donors care about. These kinds of considerations, however, are the “cart” of strategy in service of systems change: one necessary part of carrying the requisite load, but not to be put before the horse of what will effect the change in the world SJN seeks.

The first observation to make about this kind of strategy work is that it is immensely harder than the kind of traditional strategy that Bain’s formulation exemplifies. This difficulty tempts change-makers to fall into one of three easier stances toward their work:

- State a big vision and do what comes naturally, pursuing opportunities at hand on the implicit view that doing whatever presents itself that connects in some way to the big vision will ultimately result in getting there

- Seek the master plan, which specifies a detailed program of action all the way to the big goal

- Make the “transformational assertion,” focusing on some tangible, buildable solution and then asserting that this particular vehicle will effect a larger change

The first stance takes the ostrich’s approach to the hard question of how the work that “comes naturally” is causally linked to the vision. We all know that many organizations doing good work in service of good causes are building sand castles before the tide, as their work simply isn’t set in the right context to add up to significant change. The second stance tames the problem of causality. Master plans are appropriate if and only if they can be executed with confidence of achieving the desired effect. In the arena of systems change, one can almost never see all the way to the big goal, let alone plan all the steps along the path from here to there.

The third stance dances on the precipice of fanaticism. Is it good to build some new, specific, promising solution? Absolutely. And if this is one’s full goal, proceed. However, if one is pursuing a broader change in the world, one must always seek to understand the limits of what a specific solution will achieve, and determine what else is needed, in concert, to achieve the bigger goal.

Steering clear of these three traps, what should the clear-eyed change-maker look to as she shapes strategy? The seminal figures in the development of business strategy each described a dimension of business that required deep, analytical attention. BCG, in their early years, showed businesses that they needed to pay attention to the precise dynamics of the experience curve: could they gain the benefits from scale, or would they be victims of competitors gaining and exploiting these benefits faster? Michael Porter showed businesses the importance of attending to market structure. Were they, for instance, in a part of the value chain where a moat could be built and superior returns generated over time? Bartlett and Ghoshal showed businesses that they needed to have a granular, empirical view of what they were lastingly better at than competitors and how those competencies combined to generate an advantage important to customers. Similarly, advances in strategy applied to systems change will result from showing us what we need to pay close attention to, what tools we can use to see these dimensions of the world clearly and how we can act on the basis of what we see.

At Incandescent, in our research and in our work with philanthropists and social innovators, we are seeking to understand what dimensions of systems change can be defined and made actionable through frameworks analogous to BCG’s experience curves, Porter’s market structure and Bartlett and Ghoshal’s core competencies. We are, of course, in the early chapters of this work. We’ve found that six dimensions consistently surface in our work, to a degree that builds conviction that whether or not we have the right lenses and tools to address each of them, these dimensions will each be important to how the field of systems change will advance. I’ll lay these out briefly in a series of three posts, simply to provide a picture of the inquiry we’re engaged in, recognizing that each dimension merits a deeper treatment.

In this first of three posts, I’ll focus on the first two dimensions: (1) To get to the big change, what are the specific, pivotal events that are happening differently at a human level? and (2) How does one anchor this picture of human-level events in a picture of the higher levels of a complex system?

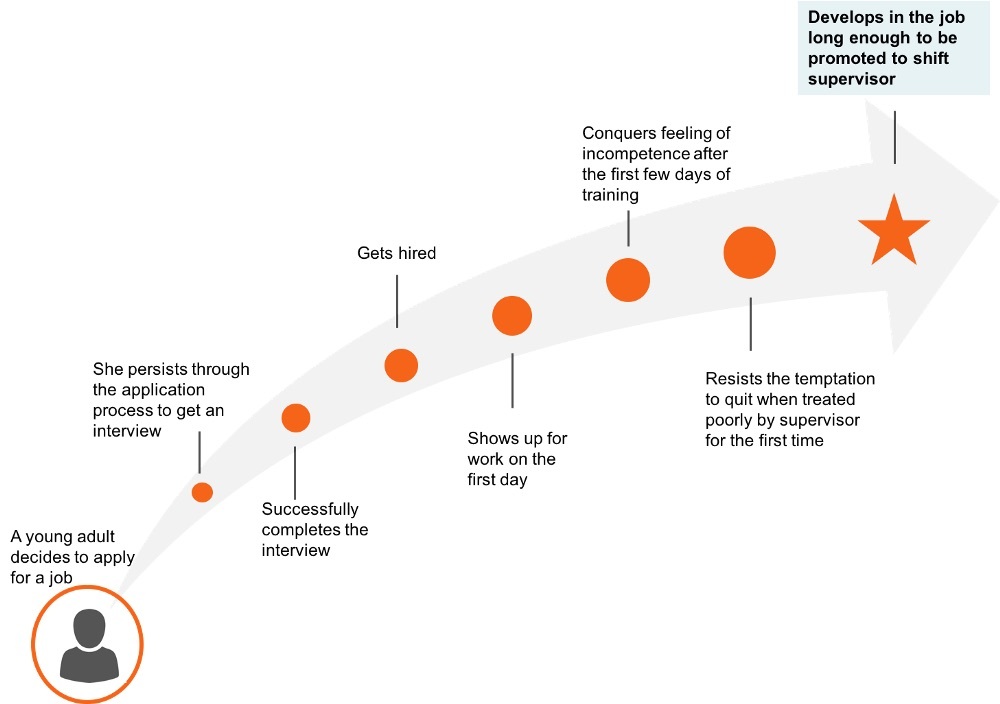

- Breaking down big change into specific, pivotal events at a human level. Most large changes are made up of many, many micro-events. A future in which a million young Americans perform a year of national service rests upon a foundation of many specific decisions, by specific young people, to serve in specific roles. Sometimes, one pivotal event – the acceptance of an offer from a service corps – stands out as the critical link, and in other cases one needs to think of an event “arc” made up of many links. In our work on youth employment with The Rockefeller Foundation, for instance, an opportunity youth achieving a sense of mastery in her job is an event arc made up of many links: the decision to apply, preparing for the interview, dealing with the many obstacles to showing up on time each day and navigating the frequent discouragements in an unfamiliar and challenging workplace, and so on, as depicted in the image below.

By anchoring our focus on one pivotal event or an event arc, we are able to think more rigorously about the causal links between elements of what we do. If a college student visits the Service Year Exchange and takes the time to engage meaningfully with the site, what specific effects will this have that will change the likelihood that he or she will commit to a year of service? If an employer like HMS Host – which manages stores like Starbucks in airports and highway rest stops – creates a program to help its managers better retain front-line employees, including the many opportunity youth who work there, what specific differences will this create in the employee experience, and how will these differences shift the curve of employee attrition? In this latter example, for there to be any movement on retention, HMS Host first needed to develop a program that would reach the front-line supervisor, then this supervisor needed to tangibly shift behaviors, then those behaviors needed to register to busy front-line employees doing demanding shift-work in airport coffeeshops and restaurants, and then those differences in employee experience needed to translate into specific people who would otherwise have quit making a decision to stay.

Attention to these challenging casual links is humbling. In our work on opportunity youth employment, funded by a grant from The Rockefeller Foundation, it was one thing to recognize the macro dynamics of the critical role of employers and to perceive the opportunity to fill a gap that many large employers were seeing regarding a lack of ways to improve the front-line management skills and behaviors that analysis showed were among the largest drivers of attrition for opportunity youth. All that counts for nothing if any of the links break. We needed data from survey questions texted to employees in O’Hare and Columbus airports to actually know if employees were experiencing a difference based on what managers were learning and trying. And even once a positive delta stood out in this data, there would be no way to know for another 180 days or so whether there was any significant shift in retention.

If we could point to a true exemplar of this focus on pivotal events, it is hard to think of a better example than Mothers Against Drunk Driving and the campaign to embed the idea of a designated driver. By focusing relentlessly on a single pivotal moment – when a group goes out for a night of socializing, does one member take on the role of “designated driver” and abstain from drinking? – and how to cause that choice to be made more often, MADD saved countless lives and embedded a lasting norm in our collective consciousness. MADD exemplifies that idea that changemakers can be missionaries, but missionaries are effective only if they have deep, granular insights into the mechanics of conversion.

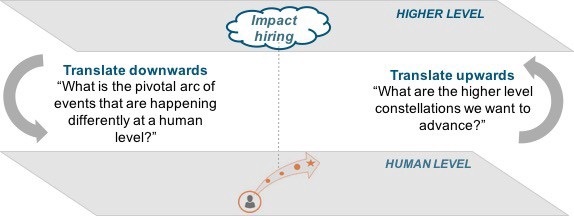

2. Connecting the human level to higher levels of a complex system. Let’s hold in our left hand this observation that efficacy requires strong causal links down at the human level of specific pivotal events: the seventeen-year-old at the party agreeing to be the designated driver or the nineteen-year-old working at the O’Hare Starbucks resisting the temptation to quit six weeks in, when the job feels overwhelming. Now, in our right hand, let’s hold what might feel like an opposite idea: often, big changes are made up of many, many specific events that form higher-level constellations of ideas. These higher-level constellations can take on broader meaning and momentum, adding up to more than the sum of their parts. With our left hand, we translate downwards from a big goal to the specific pivotal events required for impact; in our right hand, we translate upwards to the broader meaning and higher levels of change coming out of this human impact.

Our work in partnership with The Rockefeller Foundation wasn’t meant just to cause opportunity youth to be retained longer in their roles at the Columbus airport, but to advance impact hiring, which we defined as: talent practices that create business advantage through hiring and developing individuals who face barriers to economic opportunity. An opportunity youth making a certain decision in Columbus today is concrete; impact hiring is an abstract constellation of many practices conceptualized and implemented by many different companies in many different ways.

Abstraction can be immensely powerful, as a tool for understanding and as a conceptual engine for change. The specific elements of how HMS Host engages managers in airport concessions might not work at Walmart. However, the concept of how to move the needle can carry over powerfully, and that concept is all the more powerful if it is embedded in a set of mutually-reinforcing ideas about how to shape talent practices that bridge the divide to opportunity youth. Think of this as a set of nested levels of objectives that a changemaker pursues: with the youth in Columbus airport at the inner core, the program at HMS Host a level more abstract, the model of how to engage managers to achieve better front-line retention another big level of abstraction outwards, and the concept of impact hiring elevated still another level of abstraction above.

Systems change requires integrating the left-hand imperative to translate downwards, anchoring abstract aspirations in specific causal mechanisms, with the right-hand imperative to translate upwards, giving specific, human-level changes a larger meaning that makes the change stickier and more “infectious.” There’s art and science to determining where to find leverage in this layer cake of a system’s nested levels. If one could follow only a single principle here, it might be: pick the highest level at which you can translate a concept all the way down to repeatable, tangible traction. For example, one of the most important innovations of Teach for America was to leverage what we could label the “campus recruiting system” to attract star students who might otherwise never have considered teaching to teach in disadvantaged school districts. While the “campus recruiting system” is of course an abstraction, made up of many concrete components (e.g., Harvard’s Office of Career Services, McKinsey’s analyst hiring program, particular things that students at the University of Michigan say, think and do), this abstract “system” was highly actionable for TFA. This concept of how to reach talent shaped specific actions – where to go, how to present the opportunity, how to stimulate demand through selectivity, etc. – that had a high likelihood of succeeding because they went so strongly with the grain of how that system works. Part of the draw for TFA was that students could readily understand a new opportunity in terms of what the campus recruiting system had evolved to offer: here was a time-bounded, high prestige opportunity to be part of a selective peer group and learn a new set of skills, just like McKinsey or Goldman’s analyst program, but teaching in underserved districts and making a difference.

Together, dimensions one and two provide a picture of how the change we seek would occur. Dimension one brings our focus to the causal links that need to be strung together to create change at the human level. Dimension two asks us to focus on the higher-level context in which these ground-level events are anchored: what are the higher-level constellations of ideas and practices we need to advance, that will enable and spread this change?

Having a picture of how change would occur – the causal mechanisms and practical path by which today’s world could be altered – amounts to having a theory of change. Of course, “theory of change” is a common strategy and evaluation tool in the social sector. But too often, we’ve seen theories of change that articulate a vision of a better world without also articulating a core logic for how today’s world could evolve into the better one. The vision becomes a stand-in for clear thinking about the causal links and enabling contexts required. This mistake – substituting goals for a theory of how change will occur – is unfortunate, given that the theory of change approach was initially designed to foster clear strategic thinking. As Patricia Patrizi and colleagues have written, the theory of change gained traction in the early 1990s, as a way to help funders and nonprofits make explicit their assumptions and hypotheses about their work in complex social change initiatives – the links between what they did and how they believed it would create the change they sought.[1]

But even with strong attention to these two dimensions, we have only a static picture. This picture needs to be brought up against the realities of how to start from where one is – which by definition is without the necessary resources and collective of actors to achieve what’s ultimately needed. Change agents make their picture of how change occurs dynamic by attending to two other dimensions – “when” and “who”:

- They connect today’s starting point all the way to a distant destination by developing distinct disciplines for the distinct time horizons involved in a long journey

- They develop a more powerful collective of actors by forming different “we’s” to drive action, reflecting the right balance of cohesion, reach and sustainability

These dimensions also need to combine with a strong orientation toward learning. Change agents will inevitably face impasses in systems change work, when they don’t know how to move forward to achieve their most important goals, or when they need to revise their picture of how change will occur. These moments require learning and discovery, acquiring ideas and experiences that can yield new insights.

In the following two posts, I’ll explore these dimensions of “when,” “who,” and learning to get unstuck

[1] Patrizi, P., EH Thompson, J. Coffman, and T. Beer. 2013. Eyes wide open: Learning as strategy under conditions of complexity and uncertainty. The Foundation Review 5(3): 7