Even in very sophisticated companies, talent strategy often consists simply of a collection of lists.

- A list of the highest-priority enterprise HR initiatives

- Lists of people associated with key succession plans, with specific moves identified for a subset of these people

Of course, these are important lists to consider, but they don’t constitute a talent strategy, any more than a collection of budgets and a list of deals constitute a business strategy.

In order to define positively what a talent strategy consists of, let’s begin with the question of what strategic clarity consists of, in any domain:

- Clarity about commitments: what are the critical outcomes, which outcomes matter more than others

- Articulation of a small number of concepts that together establish a compelling picture of how the outcomes will be delivered. Tight reasoning connects the core concepts of the strategy to an understanding of the essential challenges and dynamics the organization faces

- Translation of concepts into specific choices, such that the small number of concepts drive cohesive focus and action across the organization, sustained over time

Richard Rumelt distills this in Good Strategy / Bad Strategy. He writes: “The core of strategy work is always the same: discovering the critical factors in a situation and designing a way of coordinating and focusing actions to deal with those factors.” He contrasts this with the prevalent pathology of bad strategy, which names goals and proffers slogans, but doesn’t establish a clear and tight connection between a substantive result – overcoming a challenge, realizing an opportunity -- and how that result will be achieved.

To apply this standard to the field of HR, I’d propose the following definition.

Talent strategy pinpoints how people, organization and culture position a business to win and defines how to achieve a lasting advantage across these specific dimensions.

In our experience, few companies meet this bar. Achieving this standard takes us far beyond “XYZ Corporation will be the employer of choice in our industry” and into a granular view of what distinctive talent outcomes fuel the specific business advantages that drive the business’s right to win. An important observation here is that for a company that plays in multiple businesses, there may or may not be a single talent strategy that connects to how all of the businesses win. Often distinct businesses will require meaningfully different talent strategies, even as there are ways the enterprise needs to operate consistently to create coherence across the portfolio. While P & G may have a talent strategy at the enterprise level that drives success across categories, Walmart needs fundamentally different talent strategies for e-commerce and for stores.

To get more specific about the patterns of what good talent strategies include, let’s begin with an analogy to a different category of strategy questions: how brands are positioned. A brand positioning statement typically follows a clear logical path:

A. To [a target audience]

THIS BRAND

B. Is the [category in which the brand is positioned]

C. That [differentiated functional benefit]

D. Because [short list of proof points, reasons to believe]

E. So that [deeper emotional benefit]

These elements can then form a clear, logical statement: To (A), THIS BRAND is the (B) that delivers (C) because (D) so that (E).

While a brand positioning can go wrong in any number of ways – e.g., the target audience is too broad or too narrow, the functional benefits aren’t sufficiently valued, the audience doesn’t actually experience a deeper emotional benefit – the framework helps the architects of the positioning reason well about this full range of issues. Marketers, whether they use this particular framework or a variation, generally have a strong understanding of the different components of a brand positioning, and as a result the average quality of brand strategies is fairly high. The road to a higher average quality of talent strategies is to establish an equivalent level of clarity about the moving parts.

Taking inspiration from the analogy to a brand positioning, consider framing a talent strategy in the following way:

A. For [business, function or population that is the focus of the talent strategy]

B. We will deliver [key business advantages, integral to the overall business strategy]

C. By [a small set of mutually reinforcing concepts and priorities that are the intellectual core of the talent strategy, where these address high-leverage aspects of the organization’s portfolio of talent, how that talent is deployed and brought together into teams, and how that talent is woven together at the level of organization and culture]

D. Which requires [how the strategy translates into design choices, disciplines and initiatives that move the organization forward]

E. So that [visualization of the way the talent strategy moves the needle on the business result in (B) and the observable outcomes we expect]

These elements form a clear talent strategy logic: For business (A), we will deliver advantages (B), by the talent strategy (C), which requires actions and decisions (D), so that outcomes (E).

Element (C) articulates the essence of the talent strategy, which is linked to a business purpose ((B) “we will deliver”) and a critical few tactical levers ((D) “which requires”), with a clear picture of how the gears of the strategy work together to deliver the result ((E) “so that”). A strategy that brings these components together into a powerful whole creates an engine to achieve a strategic result.

One of the first observations that follows from considering the logical flow framed above is that any talent strategy needs to be anchored in clarity about specific business advantages that: (a) are strategically critical, (b) significantly depend on talent, (c) with the right talent strategy, are able to deliver meaningful competitive differentiation. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the business strategy needs to be fully worked out, but it does mean that there are hand-holds in the business strategy that the talent strategy can grab onto.

In some cases, the talent strategy itself constitutes a large part of the business strategy. For instance, throughout the history of Southwest Airlines, pillars of the business strategy have included:

- Hiring people and building a culture that delivers a fun customer experience that competitors can’t and generally don’t even attempt to replicate

- Breaking down the silos between roles in a way that enables Southwest to achieve operational results that competitors can’t match (e.g., pilots collaborating with flight attendants to turn planes quickly)

- Building a culture of deep focus and emotional commitment to achieving low cost as a way to fulfill the higher purpose of “freedom to fly”

These go hand in hand with other pillars of the strategy that relate to product (e.g., no frills), process (e.g., how they board planes) and operations (e.g., point-to-point flights versus use of hubs; standardization of the fleet).

In other cases, talent strategy supports and enables a business strategy, without being as much in the foreground of what the strategy is as it is in the example of Southwest. A supporting talent strategy can be just as hard-edged and just as differentiated as a talent strategy that’s explicitly framed as a differentiator to customers. Take, for example, the 3M commitment to giving employees 15% of their time to invest as they see fit in experimental work to generate innovation. This, combined with interdependent choices about who they hire, how they create a culture of innovation, and so on, represents a highly differentiated talent strategy that supports a business strategy of product innovation, in which excellence in a set of technical domains (e.g., adhesives) is connected to a set of end-user markets (e.g., office work, healthcare).

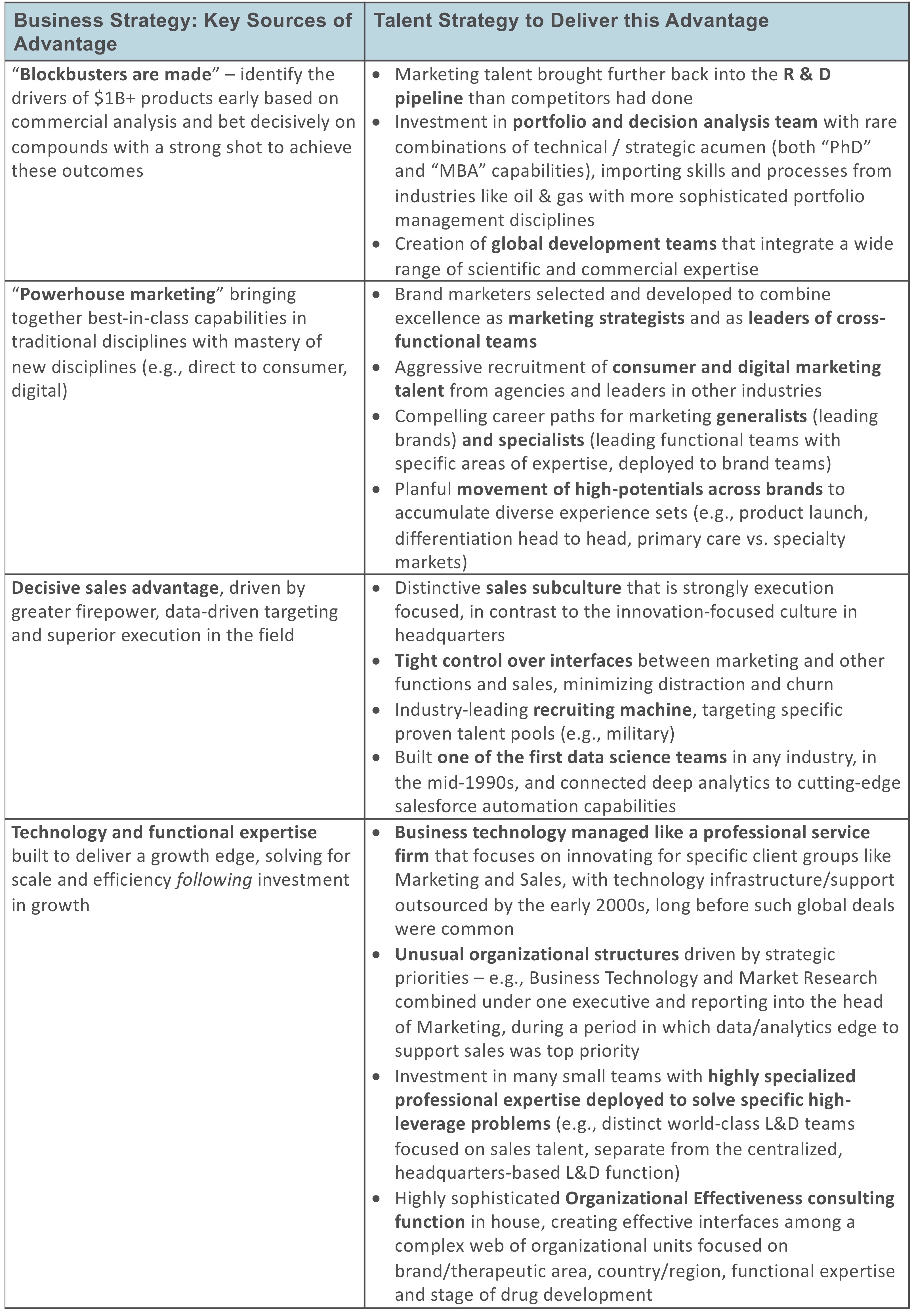

From the mid-1990s through the early 2000s, Pfizer rapidly moved from number eight to number one in the pharmaceuticals industry. How Pfizer matched talent strategies to their critical drivers of business advantage was essential to their rapid ascent to industry leadership.

As with most business strategies, these sources of advantage dissipated over time. All major pharmaceuticals companies, for instance, have since adopted versions of Pfizer’s practices to bring marketing capabilities earlier in the drug development pipeline and use data science to drive sales. Pfizer’s talent strategy has evolved significantly as a result of these changing competitive dynamics, and is no longer as distinctive, considered in contrast to the talent strategies of its major competitors, as it was during this period fifteen to twenty-five years ago. Without this investment in building critical capabilities far ahead of competitors, however, Pfizer would likely never have achieved the #1 position in global market share that it continues to hold today.

What should stand out most from the Pfizer example, alongside the examples of Southwest and 3M, is that the talent strategies were not generic “best practices.” Each of these companies identified specific drivers of business advantage and adopted talent strategies that advanced these specific priorities. Effective talent strategies translate clarity about “what we will deliver” for the business into differentiated decisions about talent and distinctive ways of teaming, organizing and building culture. Just as great brands translate a small number of core ideas that make up a positioning statement into cohesive, powerful marketing programs, great talent strategies translate core ideas about how they deliver business advantage into action. Great talent strategies embrace the intellectual work of linking business strategy to specific talent drivers that deliver advantages competitors can’t or won’t replicate, and they embrace the tactical work of translating these strategies down to the level of specific people decisions made day-by-day in the fabric of running the business. Great talent strategies, as defined by this standard are exceedingly rare – and this rarity only increases their value, as one of the competitive weapons least likely to be copied well.