Great strategists elevate organizations. They see the statue in the marble of the circumstances they face. They gain an understanding, both through analytics and judgment, of the very edge of what an enterprise can achieve — and they push the organization toward this frontier.

While an immense amount has been written about the subject of strategy, much less thinking has been done about how strategists elevate their own development: how people learn to become good strategists and how good strategists get better. This question has been one of my central professional concerns for more than twenty years. As we built Katzenbach Partners from three partners in a brownstone in 1998 to 150 people and $50m in revenues before selling to Booz & Company in 2009, we wrestled with how our people could develop as strategists without having the resources of a global strategy firm to draw upon. At Booz, I served as part of the group charged with evaluating and developing the firm’s most senior partners, where I had the opportunity to reflect on which of these accomplished leaders were continuing to learn and grow, and why. Over the course of my work at Katzenbach, Booz, and now Incandescent, I’ve made a discipline of observing how clients of different kinds — founders and CEOs as well as professional strategists — have developed their capacities for strategic thinking. Most of all, I’ve tried to mine my own journey of developing as a strategist, a journey that’s included an awful lot of failures.

If one could draw on only one concept to understand how people get better at any kind of endeavor, a good starting place would be the concept of deliberate practice, developed by Anders Ericsson and others. Geoff Colvin, in his book Talent is Overrated, describes deliberate practice in the following way:

Deliberate practice is characterized by several elements, each worth examining. It is activity designed specifically to improve performance, often with a teacher’s help; it can be repeated a lot; feedback on results is continuously available; it’s highly demanding mentally, whether the activity is purely intellectual, such as chess or business-related activities, or heavily physical, such as sports; and it isn’t much fun.

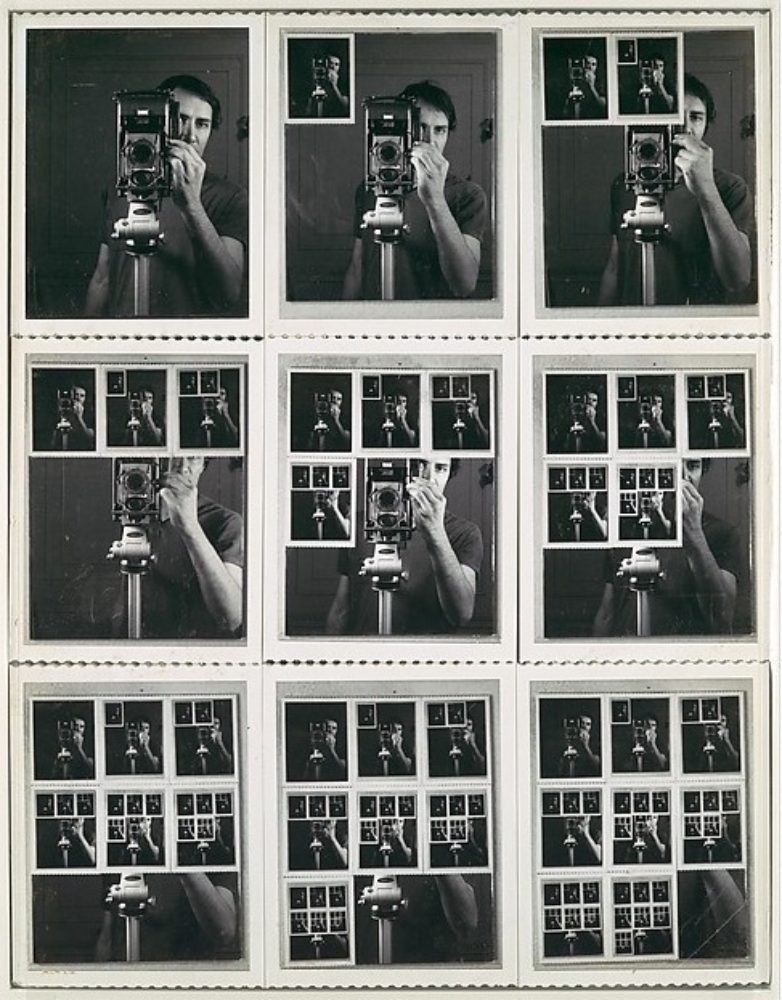

…. While the best methods of development are constantly changing, they’re always built around a central principle: They’re meant to stretch the individual beyond his or her current abilities. That may sound obvious, but most of us don’t do it in the activities we think of as practice. At the driving range or at the piano, most of us, as adults, are just doing what we’ve done before and hoping to maintain the level of performance that we probably reached long ago.

By contrast, deliberate practice requires that one identify certain sharply defined elements of performance that need to be improved, and then work intently on them…. Tiger Woods has been seen to drop golf balls into a sand trap and step on them, then practice shots from that near-impossible lie. The great performers isolate remarkably specific aspects of what they do and focus on just those things until they are improved; then it’s on to the next aspect….

Deliberate practice is above all an effort of focus and concentration. That is what makes it “deliberate,” as distinct from the mindless playing of scales or hitting of tennis balls that most people engage in. Continually seeking exactly those elements of performance that are unsatisfactory and then trying one’s hardest to make them better places enormous strains on anyone’s mental abilities. The work is so great that it seems no one can sustain it for very long….

Instead of doing what we’re good at, we insistently seek out what we’re not good at. Then we identify the painful, difficult activities that will make us better and do those things over and over. After each repetition, we force ourselves to see — or get others to tell us — exactly what still isn’t right so we can repeat the most painful and difficult parts of what we’ve done. We continue that process until we’re mentally exhausted.

Strategy is a field that doesn’t easily lend itself to deliberate practice. There’s a long lag between decisions and results, so one lacks the feedback loop that comes from hitting a golf ball or making a move in chess. Causality is complex. It is hard to disentangle the rightness or wrongness of strategy from the myriad other factors at work in producing outcomes. The work is typically shaped by many people. One typically doesn’t repeat the same kind of strategy work often. If one believes that people largely achieve mastery through a discipline like deliberate practice, these observations about strategy suggest it is likely to be a field in which few achieve mastery.

In the face of all these structural factors, some individuals do become accomplished strategists. At this early point in our inquiry into the education of a strategist, five themes stand out as pivotal elements of how people learn this difficult and demanding body of craft.

- Applying multiple mental models to a complex problem, creating a new synthesis of how to create value that integrates insights that arise from different lenses. Great strategists shape their insights by integrating perspectives that might otherwise slide past each other (seeing a problem as X vs. seeing a problem as Y) and from staying patiently with what others experience to be contradictions, tensions and trade-offs.

- Translating distant visions into present action, breaking down aspirations that reach beyond what can be achieved with current capabilities and resources into journeys that can be navigated in multiple eras, each era requiring the organization to stretch beyond its comfort zone, but just within its true limits. Great strategists figure out how to use the work required to address the imperatives of today to shape the capabilities and insights required to achieve more in the next leg of the journey.

- Managing process as an intellectual discipline that capitalizes on intellectual division of labor. Mediocre strategists let their work be driven by process, and often find the work of planning pulls them away from the larger questions of strategy. Great strategists recognize that the larger questions exceed the limits of their own understanding, and use process as a tool to uncover new facts, perceive a situation from many angles, accumulate insights that ultimately will enable a new synthesis, draw on a diverse array of perspectives, and so on. They recognize that strategy problems rarely yield to fully analytical solutions and that experts rarely have the answers, but that it is essential to make full use of analysis and expertise, each in its proper place.

- Skillfully revising one’s thinking, combining the virtues of clarity and decisiveness with the virtues of flexibility and open-mindedness. One of the traps strategists can fall into is to generate abstract ideas that aren’t falsifiable, and that create a feeling of superior big-picture understanding without being tested in the real world. Great strategists retain a clear picture of what they thought at Time X, what that meant they believed needed to be done, and what actually happened. This clarity allows a great strategist to test where the picture emerging from unfolding events might require a revision of big ideas or a rethinking of the path to execute those ideas.

- Development over the long arc: “becoming the perfect instrument.” Strategists can become dizzyingly busy staffing the leaders they work with, whether their clients are on the inside or the outside. General managers are often tempted to put strategy in a box, confining it within a process or delegating the thought work to advisors. These traps may or may not stand in the way of getting any one piece of strategy work done well, but they’re deadly in terms of the more difficult, longer path of becoming a great strategist. Great strategists put themselves in service of a larger purpose, for which they aim to become a “perfect instrument,” to use Aravind founder Govindappa Venkataswamy’s beautiful phrase. They recognize that this process of self-development is gradual, and requires mindful focus on not just the answer to each question at hand, but on the learning that each chapter of work can generate.

Building on this early list, we’ve begun to more purposefully engage in learning from individuals who are in a sense professional strategists, whether this is most of their job (e.g., within a corporate strategy group or as a management consultant) or simply one pivotal element of their jobs (e.g., as a general manager or leadership team member). We’ve begun posing four sets of questions as a vehicle for reflection:

- Aspiration. What would it look like to be one giant step further advanced in your own development as a strategist? Where would you be stronger? How would you think differently? Where would your work have greater impact?

- Looking Back. What have been the pivotal moments in your development as a strategist? What experiences, what people and what ideas influenced you most? What do you think it was about these few pivotal moments that made them so powerful?

- Introspection. What are the greatest strengths that you bring to your work as a strategist? If you look at how you think and how you work in contrast to your peers, where is your approach most divergent? To what extent do you believe developing to the next level will be about further refining and leveraging these areas of most distinctive strength — and to what extent do you think it will be about addressing weaknesses and blind spots?

- Learning Context. What are the situations you are in now or that you envision moving into soon that have the greatest potential to stretch and develop you? When you zoom in from the larger grain of the major projects and job responsibilities you have to the finer grain of specific questions, ideas, and people you work with daily, do you see opportunities to create a “practice field” for the areas it will be most valuable for you to work on? Are there situations and challenges that you aren’t currently getting exposed to that you think might be valuable to accelerating your development as a strategist?

I’d love to hear from readers who are interested in taking time to reflect on these questions, and would readily commit to having a member of our research team conduct a structured interview and share a synthesis with strategists who think they would benefit from this way of sharpening their own focus on development.

A number of posts here at On Human Enterprise relate to this long-term inquiry, including How to Revise One’s Thinking, Worldly Wisdom in 80 Models, How to Think about the Future, and Admit Ignorance! Ask Dumb Questions!. I’ll share further nuggets and reflections as our research continues to progress.

Athletes and musicians spend far more time practicing and seeking to improve than they do performing. In business, most people apply 100x or 1000x more effort to moving the ball forward based on how good they are right now than they do on the work of getting better. That’s almost never a path to greatness. Especially as one reaches the upper levels of mastery in a field like strategy, the value of getting even better elevates exponentially. Few investments return as much as deliberate charting of one’s own education. For strategists, this investment is all the more critical because the excellence of one’s own work is so often inseparable from the art of teaching and developing others. The best strategists aren’t just incisive thinkers, but orchestrators of how a group of leaders learns to think in new ways together.

A strategist who focuses on producing, producing, producing and neglects her education is like a violinist who only picks up the instrument in the concert hall. She might use the rest of her time in a range of admirable ways. She might play serviceably on any given night, but she’ll never play memorably, never play in ways that change our lives. Great strategies do change our lives, and great strategists know that this standard without exception requires them to become better than they are today.