Anyone who has built a company knows what it’s like to flip back and forth between just knowing that what they’ve pictured in their head really will get realized in the world – and despairing that the latest just-maybe-insurmountable obstacle could derail the venture entirely.

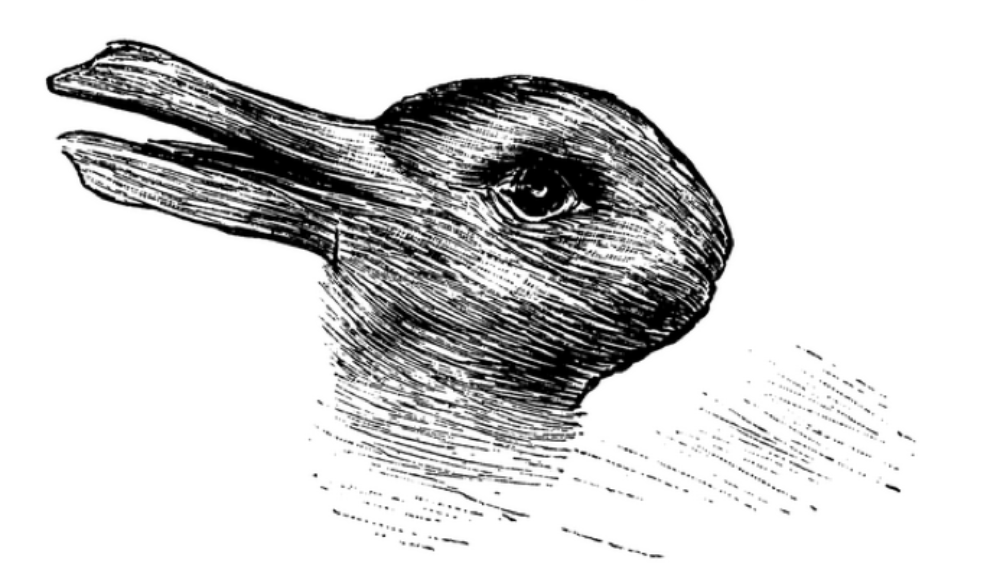

In his Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein writes about the “duck-rabbit” picture. We can see either animal at any time, but can truly see it as both at once. Similarly, the practice of entrepreneurship has two sides that can be very difficult to experience together:

- The conviction that the ultimate goal can and will be achieved, inspiring purposeful, decisive action toward that distant future

- Self-critical assessment that acknowledges what is likely to be required to achieve the goal—the ability to regard with clinical accuracy the immense gap between those requirements and one’s current resources, capabilities and vision

Seeing the world through only one of these aspects invites hubris on the one hand or resignation on the other. The art of entrepreneurship in the service of any truly large aspiration—any goal big enough that one inevitably can’t know “how to get there from here”—is about keeping both of these aspects alive, and using each in its proper way.

At Incandescent, we call visionary conviction “duck,” and eyes-wide-open skepticism “rabbit.” One of our central conversations about our own entrepreneurialism and about the founders we work with concerns the balance of these two elements, the duck and the rabbit. Too much duck looks like Theranos: a truly compelling vision about the future of diagnostics, transmuted into massive valuations ($9B at peak), landmark deals (Walgreens, Safeway), a board of directors rivaling in eminence any of the Fortune 100 – and a reality documented in severely critical reports from CMS and the FDA, and now criminal investigations. Too much rabbit and an entrepreneurial venture never gets launched at all – or looks like Larry Page and Sergey Brin haggling with Excite over a sale price for Google of $750,000 in 1999, which thankfully for them the Excite CEO turned down. “Duck thinking” doesn’t need to be hype. “Rabbit thinking” doesn’t need to be counter-entrepreneurial. Take for example, this famous moment Andy Grove describes in Only the Paranoid Survive:

I remember a time in the middle of 1985, after this aimless wandering had been going on for almost a year. I was in my office with Intel’s chairman and CEO, Gordon Moore, and we were discussing our quandary. Our mood was downbeat. I looked out the window at the Ferris Wheel of the Great America amusement park revolving in the distance, then I turned back to Gordon and asked, “If we got kicked out and the board brought in a new CEO, what do you think he would do?” Gordon answered without hesitation, “He would get us out of memories.” I stared at him, numb, then said, “Why don’t you and I walk out the door, come back in and do it ourselves?”

Of course this moment of decisive sobriety didn’t in itself build the modern Intel. Betting that Intel could build a consumer brand with “Intel inside” was pure duck: conviction in the absence of any direct precedent in the industry.

Clarity around commitments and core concepts helps the entrepreneur manage the dance between duck and rabbit. Having commitments that are few in number, deeply held, clearly stated and magnetic to others is immensely powerful as a motivating force for entrepreneurs. But these commitments by themselves don’t clarify action. Concepts play that clarifying role. The operational clarity that comes from a clear set of strategic concepts provides an arena in which one can be constructively self-critical. One can see the gap between the current way of operating and a vivid picture of how to deliver on the big goal. With that gap clearly in mind, one can make the best choices available about what to do: where doing what comes naturally is good enough, and where there needs to be a more radical search for a better way.

Elon Musk shows us what it looks like to integrate an exceptionally strong duck mind and an exceptionally strong rabbit mind. Here’s a quote from Musk in The New York Times in 2006. At this point in his journey, it’s been five years since he imagined the Mars Oasis, traveled to Russia to see about buying rockets and decided to build his own. He’s sunk $100m of his own money into the venture. He’s still two years away from the successful launch of Falcon 1. He’s in a state of Epic Duck. But he’s also got his head down, he’s entirely focused on cost and modularity. Musk explains:

“The Merlin is much more analogous to a truck engine than a sports car engine, which is how all other engines are designed,” he said. “Instead of designing it to the bleeding edge of performance and drawing out every last ounce of thrust, we designed Merlin to be easy to build, easy to fix and robust. It can take a beating and still keep going.”

He’s looking at the data of each aspect of his engine, with a just-the-facts sobriety that would make Andy Grove proud. He’s Deep Rabbit.

The art of entrepreneurship is the art of the toggle. Duck, rabbit, duck, rabbit – dizzying, certainly, but there’s a rocket to be built, an industry to be changed, a crisis to be averted, and a thousand details that need to be taken, each in turn, and each in light of a larger whole.