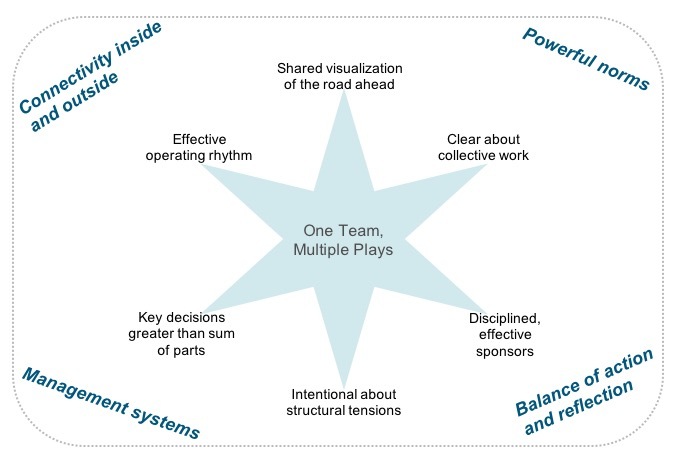

In my last post, I wrote about the six elements for excellence as a top leadership team steering an enterprise. These six elements need to be built on the right foundations, represented by the italicized points in the “ground” beneath the “figure” of the star.

Most crucially, leadership teams must have a set of powerful norms held deeply enough to override the forces that pull members away from the difficult work of enterprise leadership. Generally, executives are on a leadership team because they occupy a role of immense individual responsibility: running a business or running a critical function of the enterprise. If goals are set ambitiously, it will often feel to a leader that simply delivering on her goals and her strategies demands everything she has – and this will be at the core of her focus as she engages with colleagues on the leadership team. The leadership team, and the CEO particularly, will also feel like one of the most important, perhaps the most important audience for a top leader. These are the stakeholders who will evaluate the leader’s success, shape his future opportunities and whose support will be required to achieve his goals. In this context, it is natural for leaders to feel they must project strength and confidence at all times, rather than bring team members into the vulnerabilities of what’s unknown, unsolved, broken or at risk – which is, of course, the terrain on which the fortunes of companies rise and fall.

Different teams can have distinct norms and styles. One team might strike an outside observer as “in your face” and another equally effective team might strike an outside observer as nurturing in terms of how members listen to and support one another. Regardless of style, all effective leadership teams need to embody norms that drive them to put the enterprise first when the imperatives of the whole conflict with the imperatives of the part and to do the hard work of confronting what isn’t working and what’s at risk.

Done right, the work of a leadership team should be palpably difficult, often pulling its members out of their comfort zone to the edge and at times over the edge of their current capabilities. If it isn’t this way, that’s a sign that the leadership team is staying in the shallows of decisions readily at hand, versus seeking out the work that’s uniquely theirs to do: staring at the big opportunities and big challenges that the organization isn’t fully ready or able to confront.

If a team is operating this way, it should expect to fall short often. That’s no reason to hold back – most leaders at the top recognize, at least in theory, how important it is to have a strong bias for action. But just as athletes and musicians can’t become “world class” with a diet of continuous competition or performance, a leadership team needs to examine how it is running its plays and what it would take to run those plays better. This means cultivating a bias for reflection, setting aside explicit time to break down what’s working and what isn’t, reflect on what improvement requires and develop the practice fields required to improve the relevant aspects of their game.

No leadership team operates in a vacuum, and the effectiveness of the team depends critically on organizational management systems that tee up the right decisions (while ensuring many other decisions get made at lower levels), generate the data and analysis required to decide well, and position leaders to have the breadth of knowledge and quality of peripheral vision to have a solid shot of identifying critical questions that aren’t being raised or aren’t being framed well. While the quality of management systems is its own major topic, it is important that the leadership team as sponsor ensures that the right owners have clear briefs for delivering the management systems required for the team at the top to be effective.

Much of the thinking about leadership teams looks at the team in isolation, focusing on the work of the team and the relationships among its members, but missing the team’s connectivity inside and outside. Leadership teams that are under-connected on the inside become isolated, and leadership teams whose members are connected largely inside their own organizational silos risk becoming balkanized. Effective leadership teams are made up of members who cultivate diverse connections across their own organizations. Externally, leadership team members not only need to have significant external relationships to contribute to shaping strategic opportunities, but need to build a diverse set of relationships that reach far enough outside the organization’s typical field of vision to generate a wide view of threats and opportunities.

In delineating this model – the six elements of excellence and the four foundations -- we don’t mean to imply that all of these points are equally important for any given team. When a leadership team becomes isolated and out of touch, the question of connectivity may far outweigh all the other points. If factions develop, building shared vision and translating structural tension into explicit, above-ground “right fights” and developing norms for healthy conflict are the critical medicine.

Very few leadership teams, in our experience, are anywhere near the picture of excellence painted in these two posts. This shouldn’t be surprising. Few weekend athletes train and approach the game in ways that move them toward professional levels of performance. Most leadership teams approach the question of how they team like weekend athletes – exerting themselves unsystematically in the game itself, and not giving disciplined attention to how to raise their level of play.

In our view, the effectiveness of the leadership team is a first-order question driving organizational performance – up there with whether the enterprise has a clear and compelling strategy and whether organizational design is well aligned with strategy. Like other first-order questions, this one requires ongoing, disciplined focus.

When leaders do see a need to step up their game, they are often inclined to focus first on process – e.g., the cadence and design of meetings. While each leadership team is different, as a rule of thumb, we’d suggest beginning with the work: first focusing on where there is true collective work for the leadership team as a whole and figuring out how to drive that work more effectively. Your team can leave the rest of your process as is while developing shared, lived experience of operating differently in the context of one or two questions that matter. From there, the next step is focusing on your leadership team’s role as sponsors – clearly delineating the role of sponsor and owner, gaining “meeting of the minds” about the organization’s critical briefs, and, especially, raising the clarity and effectiveness of dialogue about reds. Our experience is that pulling these two levers create value most rapidly, and establish both the shared mental models and the feeling of momentum leadership teams need in order to commit to lasting, disciplined focus on their own performance as a team.