In a prior post, we explored the heart of entrepreneurship: the pursuit of opportunity without regard to resources currently controlled, to use Howard Stevenson’s classic definition. Applying this insight to teams, my colleagues Cynthia Warner, Darko Lovrich, and I recently published Ignition Teams: Rising to the Challenges of Innovation in People + Strategy. In it, we describe a fundamentally entrepreneurial phenomenon that we’ve seen in diverse settings in our work. Groups of people—whether in corporate innovation projects, among the founding team of early-stage ventures, or among foundations and nonprofits seeking change to a seemingly intractable problem—must pursue big goals beyond their initial reach. This requires them to confront significant unknowns, develop capabilities they don’t have at the outset of their journey, and inspire others outside the team to change the way they think and act.

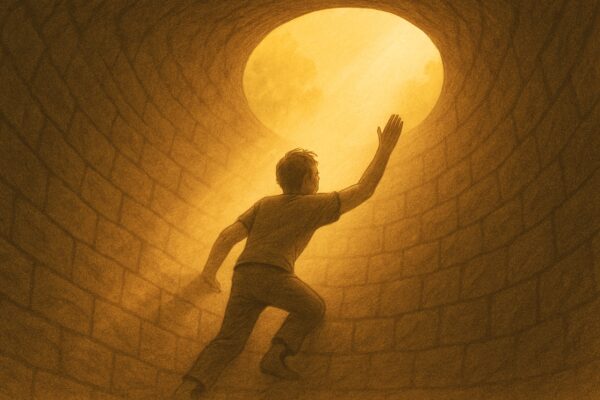

We’ve come to call teams built to face such tasks “ignition teams”: a group of people doing the hard work of creating something from nothing, as they try to bring a new product, service, or kind of impact into the world. Such teams need to author new ideas and author themselves as a team. They need to craft a path where none yet exists.

To do this, ignition teams need to achieve five balancing acts:

- Diverse team with a common commitment

- Collective intelligence without groupthink

- Bias for action but room for reflection

- Dynamic cohesion

- Lean out and lean in

For example, ignition teams need to sustain dynamic cohesion, neither settling too soon on an inadequate solution, nor splintering under the stress of challenging one another.

To “ignite,” ignition teams also need to get the world to act differently. This means leaning out to understand the needs of critical stakeholders, and then leaning in to develop an idea that incorporates the seemingly conflicting views. When it goes well, this dance of leaning out and leaning in can create a spiral of increasingly broad constellations of collaboration as the core ignition team progresses toward its goal.

The work of ignition teams is difficult. They may channel passionate optimism one moment (“we must and will achieve the goal”), but the next moment, confront with sober skepticism their current position (“we’re not yet achieving the goal and haven’t addressed these gaps”) – a dynamic we’ve explored in a previous post on the art of entrepreneurship. They can become discouraged by the enormity of what their task requires compared to what they can currently influence.

We are just at the beginning of exploring these ideas. We’d love to hear stories, examples and ideas from others engaged in learning about these same questions.