One of the biggest and most frequent mistakes of top managers in big companies is to make statements about vision and strategy that aren’t differentiating, or that they aren’t committed to translate into reality, or – more than occasionally – both.

- The fact that it is almost always a good thing for companies to focus on customer needs and customer experience

- The observation that many great companies – e.g., Apple, Southwest, Amazon, USAA to use four deservedly oft-cited examples – do excel beyond peers in the customer experience they create

- The frequency with which other sources of competitive advantage – cost leadership, a decisive technology edge, a leading premium brand – seem impossible to achieve from a given company’s starting place, while an edge in “customer centricity” seems more accessible, perhaps even without making any particularly difficult choices

It is not difficult for these factors to lead to a kind of avalanche of intuitions on a management team that becoming the “most customer-centric X company” is achievable, valuable and defensible – in other words, an excellent strategy.

This is the moment when it is important to take a deep breath of cold air.

Many of the businesses that make differentiation on customer experience a pillar of their strategy are single-brand companies. Nearly all of the successful examples of customer experience differentiation combine their “customer centricity” with another strong pillar of differentiation: Apple is a paradigm case of customer experience meets product differentiation, USAA of customer experience meets niche focus, Southwest of customer experience meets cost leadership, and Amazon of customer experience meets scale leadership.

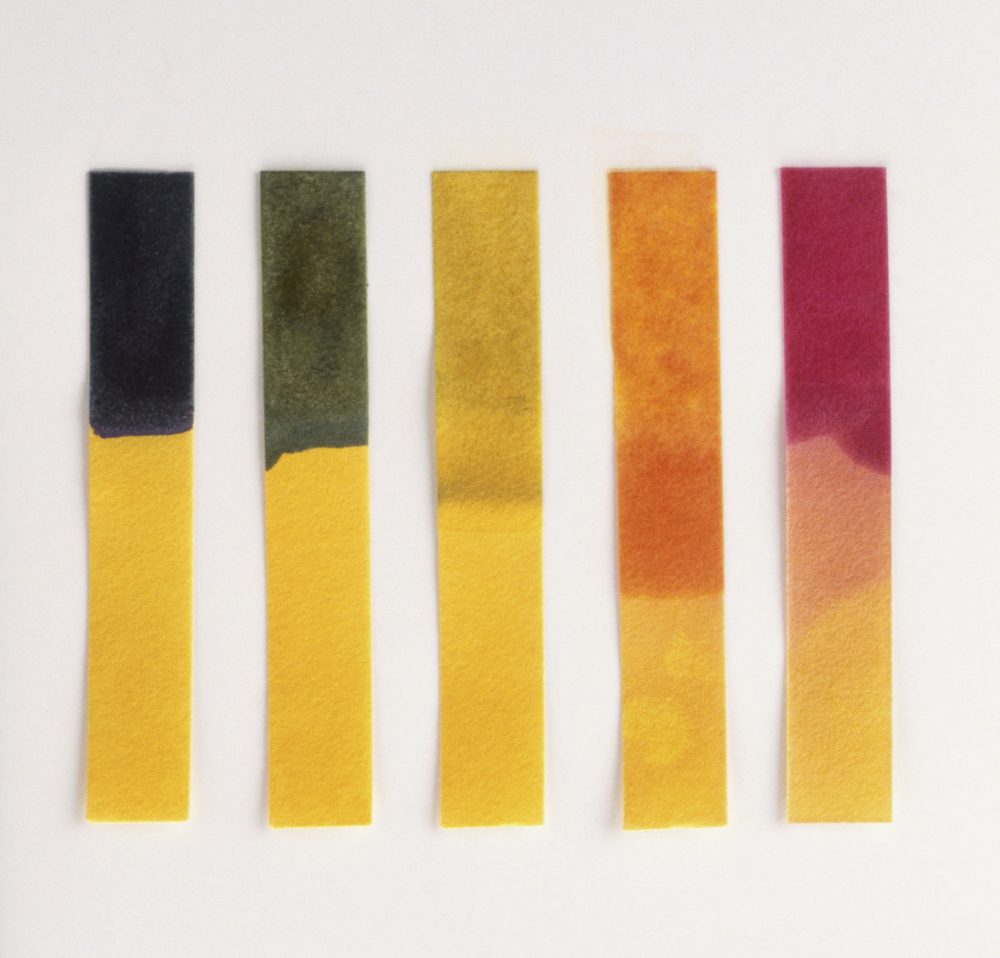

Looking at examples like these suggests three litmus tests, which should be passed before affirming “customer centricity” as a strategy:

- Identify another complementary pillar of differentiation, that will both strengthen and be strengthened by the envisioned customer experience edge

- Make choices that most competitors would consider crazy. Apple bucked the technology industry’s dominant logic of open platforms. USAA built itself on serving a single primary customer niche. Southwest ignored almost all core maxims of airline operations, like the hub and spoke model. Amazon set out on a path that involved losing very large amounts of money for quite a long time.

- Make sure that large numbers of people in the organization will be doing things differently from competitors – and generally differently from how they do things now – in ways that require unusual skill, expense and/or tolerance for risk, and therefore are unlikely to be rapidly imitated. Think: the way Southwest’s flight crews joke on the intercom, the large budgets that front-line staff at Ritz Carlton have to solve a customer problem, or Amazon’s homegrown distribution software.

I can’t prove that all successful “customer centricity” strategies pass these three tests, but my observation is that most of them do. Before, for instance, citing Four Seasons as an example of customer centric strategy, I’d recommend reading Roger Martin’s excellent chapter in The Opposable Mind on the way Four Seasons broke out of the industry’s big hotel/small hotel paradigms – a path only a little less radical than that of Southwest or Amazon in the hotel chain’s founding era.

If building a brand from the ground up to achieve lasting distinctiveness and leadership in its target market can be likened to scaling one of the many Himalayan peaks, differentiating a multi-brand company on the basis of customer centricity is more like scaling Everest. Everest can and has been scaled, but only with a great deal of preparation and energy, and never in sandals.