What I most want from my life in business is that my days be like a child’s days and that my years be like a child’s years.

A child’s days have their share of fidgeting and grumbling; stuckness and pique; but then stretches of being all the way into the task at hand: painting the water and all I can see & touch & think is blue, blue, blue.

A child's years are long. As each year sweeps along like the shadow on a sundial, it arrives at a series of marks of now it is time to: traditions to be torn into, new presents in familiar wrapping paper. And, most of all, each year brings new powers. What could be more alive than doing what I couldn’t do before, feeling what I haven’t felt before, playing where the waves break at the edge of a rising tide?

Children are given this; grown-ups must invent it for themselves.

As Incandescent turns ten, certain moments exemplify this aspiration: experiences of being fully in the flow of what we were meant to do and – equally – turning points at which we grew in some important way, not just learning something new, but entering into a larger world. I’ll share ten of these moments, nine in this post; and one, unpacked more deeply, in the post to follow.

The thought that was gripping me most deeply in the firm’s first days was about time horizons. How can we take a big vision, far beyond our grasp today, and shape a journey through the years toward this beacon? What is the role of “strategy” in the early, formative stages of an endeavor, when our powers are so limited and so much depends on tactical ingenuity and openness to serendipity? What shadow do these questions cast on the immediate question at hand for founders of “what do I do right now”?

One afternoon, David Bornstein paid me a visit, and we spent a couple of hours at a whiteboard talking about Solutions Journalism Network, which was still in its very early days. The next day, I cleared my calendar and wrote a fourteen-page memo trying to work backward from the vision of creating a whole new field of solutions journalism – as essential to the mission of journalism as “a feedback loop for society” as investigative journalism – through a series of time horizons, all the way back to the questions of today. The idea wasn’t to create a grand strategy reaching out many years, but a picture of the future that could inform and focus entrepreneurial action in the present.

Perhaps a normal response to that memo would have been “what was that?!” – but instead David and the SJN team gave us the gift of inviting us to roll up our sleeves with them in shaping their early strategy, which became a living laboratory to work through what became some of Incandescent’s core thinking, including the idea that entrepreneurial ventures develop through a series of eras, each defined by a pivotal challenge that needs to be overcome to reach the next “level of the game.”

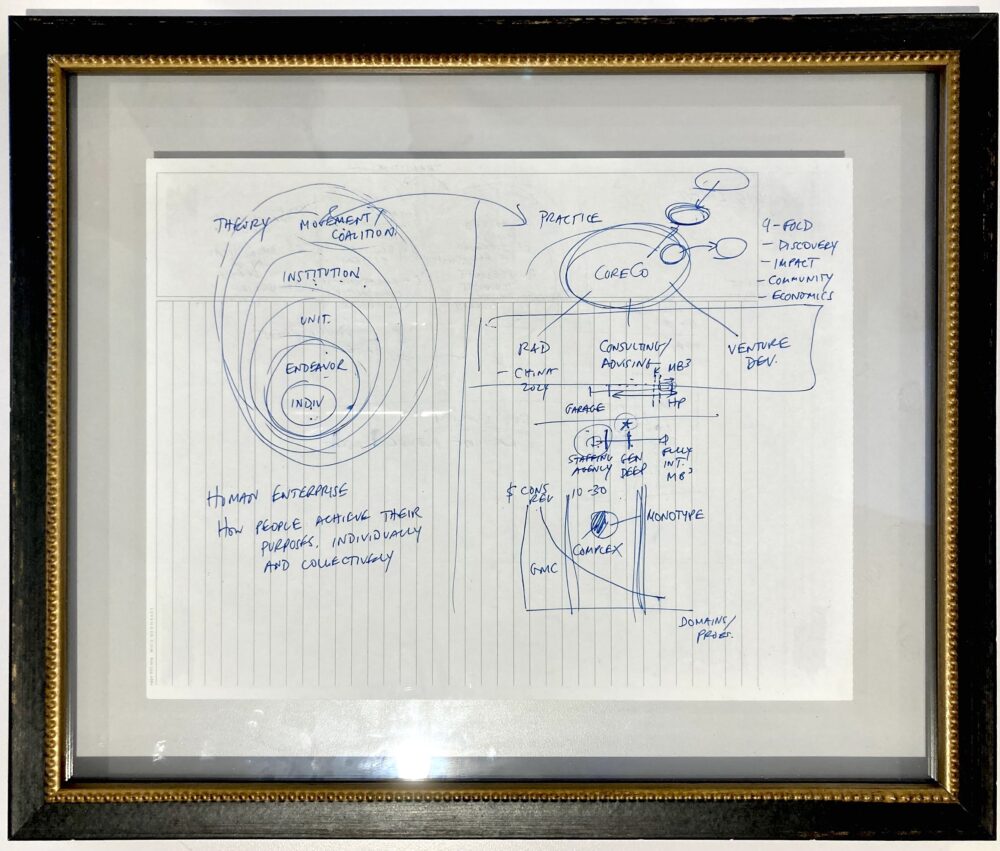

During the early months of building Incandescent – while I was still working with branding guru Jonathan Knowles to figure out what to call the firm – I had a series of “napkin sketch” conversations with different people who had been important collaborators to me over the years. These were a chance for me to develop my thinking out loud, and also a way to tie myself to the mast, by articulating a commitment to what I wanted to build. Gustavo Alba, the leading executive recruiter in the field of professional services, kept the paper I’d scribbled on at our breakfast at Balthazar and sent it to me, framed, several years after. That image frames this piece.

Ten years later, we’re living in the future that sketch envisioned. We’ve discovered a great deal we didn’t know then about what it means to think and work across the levels of the individual, the team, the unit, the enterprise, and the larger system. But the feeling remains, like in a marriage, of living the life that we intended – for all the limits of what our earlier selves might have known about how that life would be.

Part of what the napkin sketch described was that while the prior firm I’d co-founded, Katzenbach Partners, was built to work with large enterprises, Incandescent was meant to have as part of our core focus work on creating and building companies from the very early stages up. But I didn’t know how that side of the business would work.

At one of Blair Miller’s salons, I reconnected with Rachael Chong, who was at that point in the third year of building Catchafire, a platform for skills-based volunteering. We began meeting, first informally and then more formally, thinking about the entrepreneurial challenges of building a SaaS platform “where talent meets purpose,” connecting experts in every discipline to change-makers with critical problems to solve.

Rachael is among the most intentional people I’ve ever met, and her drive to be clear in her reasoning made our sessions incredibly valuable to me as a forum not just to work through problems at hand, but to map out how to navigate a range of the classic recurring challenges that come with the early stages of growth. Catchafire has since grown its revenue by 10x, and I’ve had the opportunity to be part of the company now for almost a decade, including as board chair since 2021 as we’ve transitioned in a purposeful way from Rachael’s leadership to the leadership of Matt Miszewski, a wise and seasoned CEO who shares Rachael’s founding ideals and brings a powerful playbook for scale.

Most of the business we’ve developed over the years has been through the organic evolution of relationships and informal problem solving with leaders who eventually become clients, but from time to time we’ve competed in a pitch process. The first such pitch was to work with CEO Joe Sullivan and his team at Legg Mason to help them step back and re-examine their corporate strategy.

That conversation became an opportunity for me to step back and ask: what are my fundamental beliefs about strategy?

Before turning to the pitch itself, I wrote a kind of manifesto that began by trying to define what it means to have strategic clarity (which evolved into this post) and to develop the language of 6Cs as a taxonomy of the questions that come up in shaping a strategy. It would have been unwise to assert a prescriptive view of the work with Legg Mason from the outside – in this kind of strategy effort, half the work is formulating the right questions to ask. By considering the “general case” behind the specific situation we were entering, we created a framework for rigorous exploration and ensuring that our clients would deeply drive the work of problem definition.

Children ask beautiful questions grown-ups have learned not to ask. Nothing mattered more to my development in the early years of building Incandescent than learning to be more childlike in the questions that I asked.

Consultants often feel they need to have something new to say: something the client’s never thought of before; something that exemplifies the consultant’s distinctive expertise. But what’s important is rarely new – and what’s important is usually lying in plain sight.

At first through a collaboration with my longtime friend and collaborator Jacqueline Novogratz about how to define the “Acumen Way,” I began to see more clearly something that I’d previously just treated as the water that we’re all swimming in in building organizations: how “sponsors” delegate work to “owners.” So much of what goes awry in organizations comes back to the simple and difficult act of achieving a true meeting of the minds regarding the brief, and then sustaining an open, accurate, effective dialogue as the work proceeds through its inevitable shifts and challenges.

Another related milestone came a couple of years later when, through an introduction from Kevin Cox, I found myself in an extended working session with the leadership team of a top Consumer Packaged Goods company, a team I’d never worked with before, wrestling with some complex discussions about organization design. In a way that I’d never have considered doing at Katzenbach or Booz, at an important moment in the discussion, I stepped to the whiteboard, said that I recognized that what I was about to say would no doubt feel extremely elementary, and drew two boxes labeled “sponsor,” one box labeled “owner” and a box in the middle labeled “brief,” which I unpacked as what outcomes and why, by when, subject to what constraints. I asked the group to stop and look at what was going on with each of these boxes in an example the group had been debating relating to a manufacturing and supply chain initiative.

Most of the executives in the room led organizations of thousands of people. I felt a bit like I was saying to a set of top-ranking heavyweight boxers, “hey guys, let’s talk about how you’re punching.” But if we were to talk about boxing, punching isn’t exactly a subject that could be taken for granted. It wouldn’t do just to use a bunch of terms of art, like “dotted-line reporting relationship” and draw “RACI” or “RAPID” charts (two models often used to map – exhaustively – roles and decision-making in complex organizations), and assume that the “punching” would take care of itself.

Over and over again, in those early years, I found that much of what I was learning was the courage to strip away layers of accumulated assumptions – my own and others’ – and talk about the work itself.

There has been no more important moment in the building of Incandescent than Shanti Nayak’s decision to join us in 2015 and her commitment to building a practice in systems change. In the spirit of a beginner's mind, we sought out opportunities to “treat the problem as the client,” starting from the goal of how to manifest a certain change in the world and then asking how different institutions might come together as catalysts to achieve that change. That mindset is on the other side of the looking glass from how companies – who need to focus on value capture – think about strategy, and even from much of the thinking in the non-profit sector which begins with questions about a specific organization’s differentiation from others.

In Shanti’s first week, we went all-in on applying this perspective to an opportunity to compete for work with a set of actors in the field of national service who were developing a strategy for how to achieve their shared commitment to dramatic growth in the number of young Americans who serve. Through that work, three non-profit organizations with distinct and complementary areas of focus took the leap to merge and form the Service Year Alliance. This experience taught us an indispensable lesson about what is possible when a group of committed leaders takes the perspective of the whole system, carefully working backward from their goals to understand what it will take to catalyze a big advance, and reframes the roles, even the identities, of the organizations they’ve worked so hard to build.

As Incandescent developed, we came to see more clearly how central the idea of entrepreneurial action was across the full range of our work, not just with start-ups. The corporate, foundation and non-profit executives we were working with, just as much as the founders, were reaching for goals far beyond their grasp and trying to understand how to navigate territories for which no one has a map.

To advance our understanding of the “outer game” and “inner game” as these unfold over an entrepreneur’s whole odyssey, we needed opportunities to go on the long journey with extraordinary founders to build from the spark of an idea to a transformational, enduring enterprise. I’m grateful to be on several of these journeys. None exemplifies the aspiration better than to have been in conversation with Koda Wang and Luke Sherwin as they came together to imagine and then build Block Renovation. Block will turn six later this year, and while the company has already gone further than any venture before in competing as a disruptive entrant in the $450B market for home renovation, we’re still at the beginning relative to the scale of the problem and the opportunity. Serving as an advisor throughout this journey, and a board member for much of it, has been a laboratory for learning how to stay focused on a transformational vision for the industry through all the twists and turns of each successive urgent problem that needs to be solved in building a company. One of Block’s founding principles was “problems are fuel,” and the obsessive focus on throughput the company needed to adopt at the height of the supply chain meltdowns was, in its own way, a catalyst for innovation no less than the opportunity to weave genAI into Block’s tools and business processes.

While many of these formative moments were early in Incandescent’s history, I’ll close this reflection closer to the present. Last year was an extraordinary year for us, not only by far our strongest financial performance but also a watershed in terms of the impact of our work. We were particularly proud of the launch of New Pluralists, a landmark collaboration of funders across the ideological spectrum to fight polarization in America, where Shanti played a significant role in helping the founding funders shape, steward and bring into the world. Amidst this all, the most significant event of our year was Traci Entel joining Incandescent as our third partner, reuniting with Shanti and me after a decade in HR leadership roles at Booz & Company, BlackRock, and Stripe.

In December, after a working session on some of the more mind-numbing details of our year-end close, Traci, Shanti, and I were sitting around the table in our offices near Madison Square, and Shanti said: “One of the things I’ve been thinking about is what it means that this will likely be my terminal job.” I’ve always thought about Incandescent this way, that it will be the vehicle for all the work that matters to me over the arc of 25, 30, 35 years – or whatever it might turn out to be – from founding to retirement. Traci shared that even just several months into her time with Incandescent she was thinking in a similar way.

There we were, looking at one another, with a beautiful sense of arrival, appreciating what it meant to be building the firm we aspired to build, with the people we wanted most to be building it with.

A. A. Milne introduces his book Now We Are Six by explaining:

We have been nearly three years writing this book. We began it when we were very young ... and now we are six. So, of course, bits of it seem rather baby-ish to us, almost as if they had slipped out of some other book by mistake. On page whatever-it-is there is a thing which is simply three-ish, and when we read it to ourselves just now we said, "Well, well, well," and turned over rather quickly. So we want you to know that the name of the book doesn't mean that this is us being six all the time, but that it is about as far as we've got at present, and we half think of stopping there.

Here we at Incandescent are at ten, appreciating “where we’ve got at present,” a place lovely enough that we half think of stopping here – even as we look forward to what our someday-selves might come to know, which we today have only barely glimpsed.