In the first of four posts on self management, I tried to name the distinct building blocks that constitute the foundation of a self-managing organization. After a second post characterizing the strengths and weaknesses of Holacracy, the third and most recent post laid out an architecture for self management that I believe would in many cases be a stronger alternative to Holacracy: less complex, more readily harnessed to advance an enterprise strategy. (A critic might counter: more “hierarchical” and “traditional,” less adaptable through the sum total of many lateral connections.)

The architecture I lay out has at its core a nested hierarchy of objectives passed from sponsors, responsible for breaking larger objectives into smaller ones and delegating ownership, to owners, responsible for shaping the path to the goal. Accompanying this “hierarchy of objectives without hierarchy of command” are five principles, each embodied in a set of practical disciplines, relating to how specific roles become windows into the functioning of the broader enterprise, giving each member of the organization a voice, distinguishing between decision rights and the ability to decide well, affirming the primacy of enterprise-wide goals, and consciously managing structural tensions.

These disciplines are important because they begin to bridge from architecture – in the sense of structure and process – to culture. Many discussions of self management focus far too much on architecture and imply a tighter connection between choosing an architecture and producing a culture than is generally the case. In my view, designing the best architecture is at most a third of the battle. The much larger share revolves around the consistent, difficult work required of leaders – formal and informal – to shape a culture in which the ideals of self management get realized and translate into advancement of the organization’s broader goals.

Whatever architecture for a self-managing organization is chosen, I’d propose that five litmus tests be used as indications for whether the culture of a self-managing organization is delivering what it needs to:

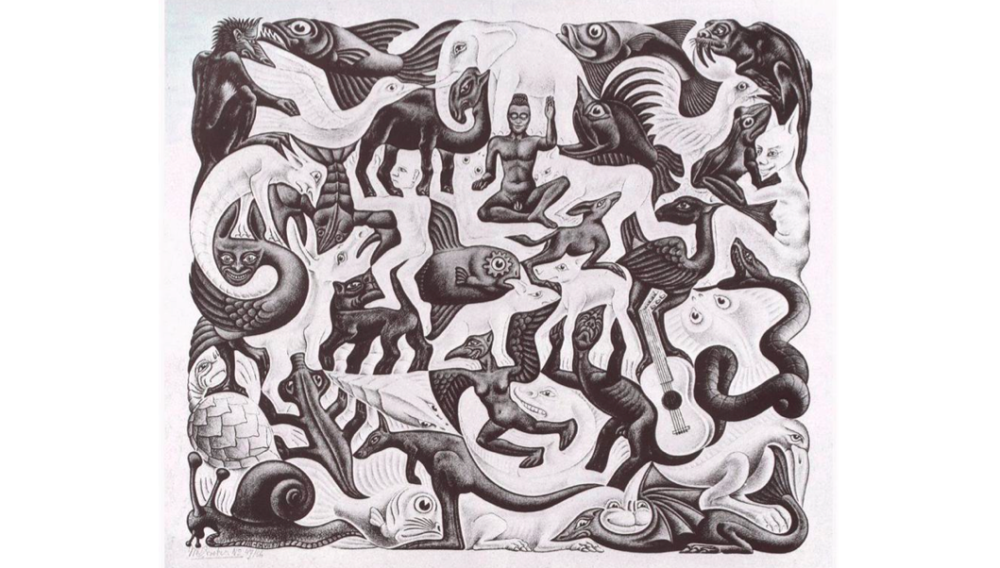

- Debating values and objectives against a shared backdrop. In self management, individuals understand themselves to have a voice in discussion of ends, not just of means. Institutions have multiple ends, some of which may be destinations (outcomes that could be achieved and completed) and others of which may be lasting values (e.g., commitments about how to operate or how not to). These multiple ends can and do come into conflict and need to be sorted out, work which is understood to be in meaningfully collective – which isn’t to say that all voices will be equal. At the same time as they encompass this divergence and debate, institutions that apply self management well have a strong shared backdrop of fundamental commitments, which are reevaluated only when there is strong reason to do so.

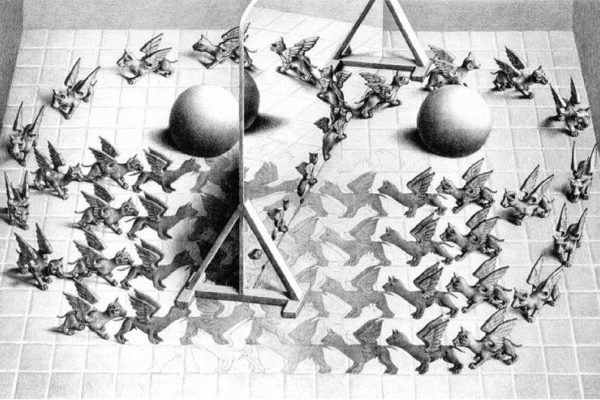

- Integrating multiple individual perspectives into a shared perspective. In institutions that apply self management well, people think together, seeking out the perspectives of others for the sake of revising their own perspectives. This can include the aggregation of facts and evidence, but also the consideration of multiple ways of thinking to find the best of these ways or create a new synthesis.

- Reflecting together on how individuals, the group and the institution are operating – and feeding implications from these reflections back into the group’s process. At the heart of effective self-management is the discipline of reflection. To fully realize the potential of self management, institutions must have standards for how to think and how to operate that are core to membership, and members who compare what they see and experience against these standards. Perceived gaps are frequently surfaced and discussed. If an important gap is identified, this leads to a conversation about changing the course of things.. While different individuals may have differing authority or credibility, no one is above being questioned with reference to the higher standard of the institution’s shared commitments.

- Reaching and affirming mutual commitment. While the architecture of sponsors and owners vests certain decisions in specific individuals, when groups deliberate together they reach shared commitment. This shared commitment translates into shared resolution to act. Institutions that harness self management effectively recognize the concept of “disagree and commit,” as they honor the individual’s need to think independently even as he or she affirms the mutuality of a decision and commitment.

- Translating the institution’s goals, norms and decisions into personal commitments and individual actions, even in the absence of direction from others. Individuals can only truly be part of the “we” of an institution if they take the institution’s goals and way of operating, including its culture, values and core decisions as giving them strong personal reasons for action, independent of specific directions or job responsibilities they have been given. While an individual can dissent, this dissent takes on a distinct meaning against the backdrop of the larger set of values and norms that the individual affirms sharing with the institution.

It may be that the architecture I propose of sponsors, owners and meeting of the minds, along with the skilled realization of the five principles, are sufficient to create a culture like this – just as it may be that the application of the process embodied in the Holacracy constitution has this effect. However, we can’t assume that will be the case. It is the responsibility of the leadership to look “from the balcony” at the enterprise as a whole and to understand and address what barriers may be holding the enterprise back from fulfilling these litmus tests. And it is the responsibility of each individual to look through the window of his or her role to see such barriers and to give voice to what he or she sees.

Just as there are night and day differences between the efficacy and cultural health of traditionally structured organizations, there will be equally large differences among self-managing organizations. In an organization in which each member takes on a facet of the work of leadership, all members need to embrace the investigation of whether the culture is equal to the organization’s intentions and its needs, and, when that standard gets compromised, to stand up for whatever is required to rectify the gap.