The best entrepreneurs begin with a commitment to something others deem impossible. This quality—call it the founder’s stance—doesn’t at root have anything to do with starting a company. At its heart, the founder’s stance is about pursuing without compromise a goal far, far beyond one’s grasp, with full understanding that only on the journey to the goal might the traveler learn the way.

At Incandescent, we have focused on playing a part in three stories:

- Entrepreneurs building ventures from the ground up

- Leaders transforming established institutions, whether from the top or as intrapreneurs pursuing big visions from the middle of large enterprises

- Catalyst organizations and coalitions working to change whole systems

Each of these demands a founder’s stance. They are different fractal scales of the same underlying odyssey: the art of undertaking the impossible, and the journey of seeing that commitment through.

When we contemplate an odyssey toward the impossible, letting our imagination roam from the safety of our point of departure, we imagine the journey’s outcome will be determined at the moments of highest stakes and greatest danger. We ask if we have the strength and the will to confront these perils.

From the safety that precedes commitment, we might imagine trials like these:

For two days and nights he was tossed by the violent waves,

and many times he thought that grim death was certain.

But when dawn brought in the third day, there was a windless

calm, and Odysseus, as he was lifted up

by the massive swell, caught sight of the shore close by.

As children rejoice when their father begins to get better

after a long, painful illness that was brought on

by some malevolent spirit, and then to their joy

the gods set him free and they know that he will recover:

just so did Odysseus rejoice when he saw the shoreline,

and he swam on, eager to set foot on solid ground.

But when he had come as close as a shout would carry

and he heard the road of the sea on the rocks as the great waves

thundered against the coast, and all things were covered

by the wash of the salt spray—for there were no harbors there

where a ship might anchor; there were just headlands that jutted

into the sea, and sheer cliffs, and jagged reefs—

Odysseus’s limbs went weak, and his heart sickened….*

Yes, along the path to a great goal we can expected to be tested in dramatic ways, and when on the other side of success we replay the highlight reel in our mind’s eye, these are the moments we’ll linger on with the greatest satisfaction.

But through long observation, I have come to believe that the true test of an entrepreneurial soul, the crux that determines success or failure, comes not in confrontation with these stark perils, but in another, quieter arena.

When we undertake the impossible, our nemesis is what we might termthe default path. Along the default path, we do what comes naturally—often with great energy, but with little fundamental reflection—and assume this will be sufficient.

The first step to overcoming any great enemy is understanding the source of its powers. The default path begins with a fuzzy commitment. This fuzzy commitment has an insidious effect. We go about our days, experiencing what we experience, and don’t feel any great contradiction between this reality and what our goal demands. To use the language of psychology, we feel little cognitive dissonance.

Without cognitive dissonance, there’s nothing to arrest the momentum of how we’re currently inclined to operate. We take the risks that feel right and prudent. We draw on the capabilities we have, acquire the resources we can, take practical steps in what we believe to be the right direction.

For goals more readily within our grasp, this might be just fine. When we undertake the impossible, however, the default path will take us nowhere near the goal. We’re lulled by the illusion that we, as we currently are, can complete the journey. This illusion is the vale of safety we must leave.

What, then, is the alternative?

I’d like to tell a story, in which one of the world’s great companies could have fallen into disrepair, but instead reinvented itself. Like all such stories, this one has many chapters. I’ll focus on a pivotal early chapter, in which the hero led from the middle of the organization, with little formal authority, limited resources, and scarcely any experiences that qualified him for the journey he came to realize he must take.**

In the late 1980s, Dennis Carter was Andy Grove’s Special Assistant for Technical Affairs at Intel. Among the glamorous duties of this job was sorting through Andy’s mail, highlighting and annotating the critical passages for his boss’s nightly review. This role gave Dennis a broad view of the company that had come to occupy a shaping role in the computing industry, developing the 286 microprocessor that was the critical component of the market-leading IBM PC and its clones, and driving the cycles of innovation that advanced the law coined by its former chairman Gordon Moore, who held that the processing power of a microchip would double every two years.

In late 1988, Intel launched its new product, the 386—which flopped. In response, Intel’s executive committee assigned a team of engineers to develop a scaled-down, significantly less expensive version of the 386. Dennis led that team. The team fulfilled its mandate, and delivered the spec. In Sally Helgesen’s chapter, Dennis recalls:

We came up with a chip we called the 386SX. For what we were trying to do, it was absolutely the perfect product—scaled down, but still a 32-bit chip. The idea was just to introduce people to 32-bitness, get them hooked on that, make 16-bit [the architecture of the 286] obsolete forever. We were so excited and proud that we’d got it right. So we put the new chip out there, and then all stood back like good little engineers and waited for it to sell. But we still couldn’t move it. No one wanted the thing—no one.

It was at this moment that Dennis resolved to take the founder’s stance. He had been assigned the brief to deliver the 386SX. He now assigned himself a much harder brief: to figure out how Intel could create demand for greater processing power, the primary output of the R & D machine at the heart of the company’s identity.

At that point of commitment, Dennis faced a bewildering array of challenges:

- He didn’t know why the 386SX had failed

- He didn’t have a background in Marketing or Sales

- He didn’t have formal authority or budget

In Howard Stevenson’s classic definition of entrepreneurship, pursuit of opportunity without resources currently controlled, Dennis was an entrepreneur. As Dennis worked his way into the problem, he came to see that the whole company was caught in the grip of a strategic dilemma. For all the glory of the role they’d played in the advance of computing, Intel found itself held in a vise.

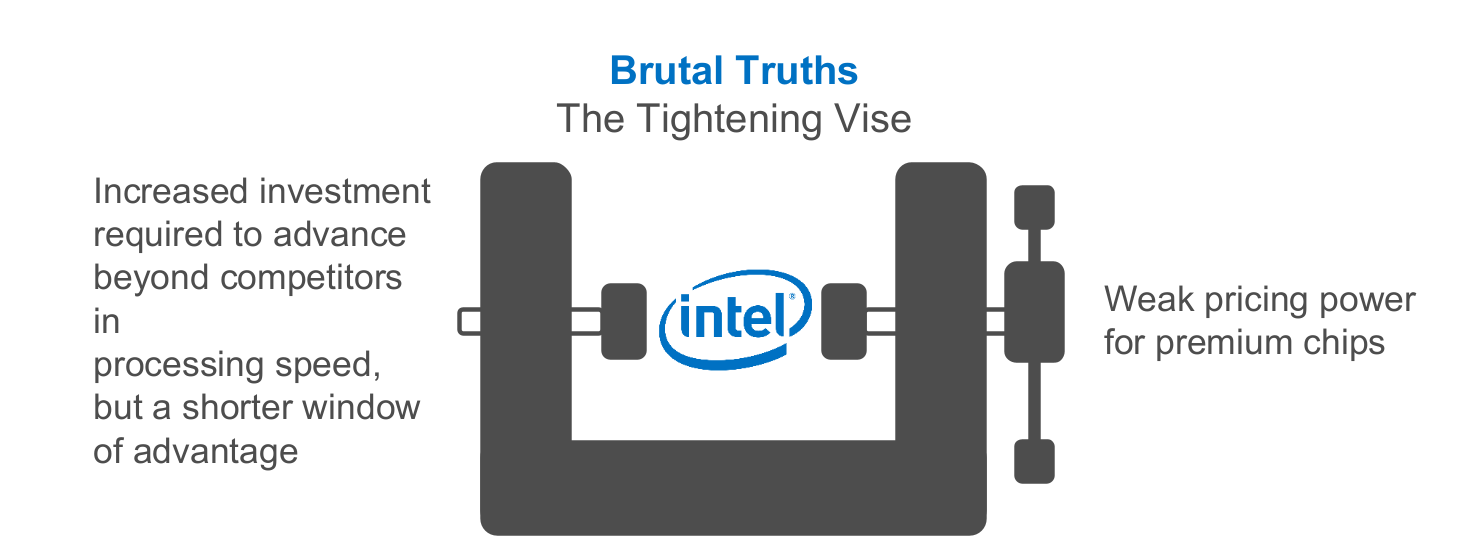

Fundamental forces were turning the vise tighter. On the one hand, Moore’s Law was operating just as Intel’s co-founder predicted it would, but the R & D investment required to drive each subsequent doubling of computing power was greater and greater. While the cost of innovation was escalating, competitors were learning to reverse engineer Intel’s chips in shorter windows of time, so Intel was spending more to secure a shorter window of advantage. On the other side of the vise was the brutal fact that Intel’s customers, the computer manufacturers, weren’t willing to pay the premium for superior performance that would make Intel’s economic equation work. The logic was inexorable. Unless something fundamental changed, escalating costs and diminished ability to extract value would break the company.

What could be done? One path would have been to acknowledge commoditization and dramatically reduce Intel’s cost structure. Executed well, that could have been a path to a moderately successful outcome. But it would have turned away from every tenet of Intel’s culture and values. Intel was a company built to shape the future, not a company built for financial optimization of the present. The default path, the path most companies in positions like Intel’s take, would have been to split the difference: cut some costs here and there, try to keep investments in innovation as intact as possible, and call all that a “transformation strategy.”

Dennis had conviction there was a bolder path. If Intel persuaded consumers that the speed of the chip was the most significant factor shaping what their computer could do, those consumers would pull the PC manufacturers to pay up for superior processing power. The vise would be broken.

The problem was that most consumers didn’t understand or care about microprocessors, and neither Intel nor anyone in the industry had any evidence that they could be made to care.

We all know how middle managers are supposed to see the world.

“I have a job to do, I’m not the CEO of the company.”

“I’m not a marketer, I’m an engineer. I wouldn’t know the first thing about marketing.”

“Be practical. The budget required to build a consumer brand in a field where there’s never been a consumer brand before would be enormous. My budget is a rounding error above zero.”

Taking the founder’s stance, Dennis saw through different eyes. Of course consumers could be persuaded that processing speed was essential—that was simply how computers work. He didn’t know how to persuade them, but that’s the kind of thing one goes and figures out. And besides, it had to be solved. That was the only way out of the vise.

But where to begin?

Dennis began the way a founder would, driven by the simple principle that there was no way on earth that Intel could build a campaign to persuade consumers of the value of his product if he couldn’t begin by persuading some consumers, somewhere that chips matter. He recruited co-founders. They were probably no one’s idea of A players who would solve a problem no one in the industry had even believed to be solvable, but they knew how to do some things Carter didn’t: Sally Fundowski, a market researcher who had left Intel, was struggling in a start-up, and had just had her second child; and Ann Lewnes, who was on the staff of Intel’s internal magazine, and was probably the closest thing to a marketer near enough at hand. The three of them went to Denver and got to work.

As Dennis described to Sally Helgesen:

When we got to town, we had no network to buyers, very little name recognition. We had to start out by walking cold into retail stores. We just went in and struck up conversations with people who made a living selling PCs. Mostly, we asked questions: we were trying to get an idea of what their customers looked for, what the dealers themselves thought their customers wanted.

If you drew a diagram of Dennis’s team in Denver it would look like a series of loops: undertake to solve some small step, advance, try a next step, get stuck, figure out a way around the obstacle, get stuck, try something else, move one small step ahead. How do we learn what dealers think matters to the buyer? How do we convey the value of the 386 in terms that connect to the dealer? Wait, that didn’t work. Can we learn other clues from the buyers themselves? Can we open the dealer’s eyes to someone that helps them sell? Can we create an effective point of sale display? What if we put up a billboard? What if we get on the radio? What if? What if? What if?

Through these messy early loops, Dennis and his ragtag team sustained the fundamental balancing act of entrepreneurship, the intellectual and emotional center of what it means to take the founder’s stance.

The practice of entrepreneurship, whether enacted by a founder in her garage or Dennis in the computer shops of Denver, has two sides that can be very difficult to experience together:

- The conviction that the ultimate goal can and will be achieved, inspiring purposeful, decisive action toward that distant future

- Self-critical assessment that acknowledges what is likely to be required to achieve the goal—the ability to regard with clinical accuracy the immense gap between those requirements and one’s current resources, capabilities, and vision

At Incandescent, we call visionary conviction “duck,” and eyes-wide-open skepticism “rabbit.” Like in the picture, which has two aspects: duck and rabbit, at any given moment, we can only see one animal, but we can learn to toggle back and forth, keeping both duck and rabbit in the foreground of our minds. Seeing the world through only one of these aspects invites hubris on the one hand or resignation on the other. The art of entrepreneurship in the service of any truly large aspiration—any goal big enough that one inevitably can’t know “how to get there from here”—is about keeping both of these aspects alive and using each in its proper way.

In those early days in Denver, Dennis used his “duck” mind to work backwards from the big goal.

- For Intel to build a consumer brand and escape the vise, first, top management would need to have seen a sufficiently compelling demonstration of results to make a very big bet

- To get the resources and buy in for that demonstration case, and to be confident it would work—because there would only be one try—first we’d need to be able to move the needle on consumer engagement and demand at the scale of one city

- To move the needle at the level of a city, we’d need to develop a set of effective tactics that we can weave together into an impactful campaign

- To develop those effective tactics, first we’d need to understand what matters to consumers and dealers, and develop messages that we can see resonate, at an individual one-to-one level

This process of thinking backwards makes clear the path of ascent, through which goals at a seemingly impossibly high level of elevation—a breakthrough consumer brand, in a category where that’s never existed—can be broken down into a climb that can be executed in stages. The links in this chain create a structure like levels in a game. The prize for completing level six of the game is that Intel is successfully on the journey to build a breakthrough consumer brand, the foundation for still further levels of the game. To get there, one must complete level one—sufficient understanding to land the message that chips matter, one to one and face to face—which opens up the second level of effective tactics, then the third level of a campaign that moves the needle in Denver, to the fourth level of a successful large-scale journey, to the fifth level of gaining top management support for a national campaign. Looking out into the future with rabbit eyes established a clear roadmap that if Dennis wanted Intel to have completed level 6 within a year, he and his team would need to complete the earlier levels of the game at a furious pace.

For Dennis and his team in their early days in Denver, however, there was a yawning gap between that timeline and their reality. They were stuck at level one, and the only way to move forward at all was to solve a problem that they did not know how to solve. For instance: how, exactly, could they create a point-of-sale display that would successfully replicate the fleeting success they experienced in the best conversations they had with the customers they cornered in the store aisles? None of them had ever developed a point-of-sale display for anything, and no one in the world had ever developed a point-of-sale display for the microprocessor inside a PC. The rabbit mind sees this challenge clearly, practically, unsentimentally—with full recognition that the coffee-stained draft in the folder just opened is nowhere close to good enough.

If Dennis Carter’s story were made into a movie, much of the action we’d experience would be this long series of scenes in Denver; those early months were the crucible in which Dennis and his team needed to solve the fundamental problem of how to make Intel’s 386 chip relevant to the end consumer. By the time the team left Denver, they knew the problem could be solved—what remained was a question of scale. (To minimize the difficulty of scale would be like thinking that it’s simple to go from having a thousand dollars in the bank to being a billionaire—it’s just a matter of adding zeros.)

Just like in a movie, the nature of the drama shifts from act to act. As the team progressed from Denver to a twelve-city demonstration case, the heart of the action shifted from figuring out how to persuade the end customer to engaging the organization to deliver effectively at this larger scale and demonstrating to top leaders that Intel could land a national campaign. This shifting action required new players and new moves. The “we” expanded from the crew of Dennis, Sally and Ann in Denver to a larger cast of characters, and CEO Andy Grove, who had backed Dennis’s endeavor from the beginning, became more central to the action.

The movie’s denouement plays out in the boardroom. The point of decision has come regarding the launch of Intel’s first consumer ad campaign—the first such campaign in the semiconductor industry. Dennis and his team have worked with an agency and formulated a campaign so risky, so inflammatory that after the campaign launched, USA Today ran a front-page editorial denouncing its stupidity. The campaign was called the Red X. In the first advertisement, Intel spray paints a giant red X across the number 286, the product that, at the moment the ad ran, accounted for the majority of Intel’s revenues. The ads that followed then presented the benefits of the 386. For all the drama of the decision—can we bet the company that when we torpedo our best-selling product, we’ll drive adoption of our more expensive, next generation chip?—the decision has already been made. The logic is inexorable. Drive adoption of new generations of chips at the speed of Moore’s Law or perish slowly in the tightening vise of commoditization. We see a flashback: Andy Grove recalling when he was #2 and he and Gordon Moore confronted the decision about whether to get Intel out of memory chips, as the tide of foreign competition rose for what had become a commodity product. The decision is made, the Red X runs, the die is cast.

For all the drama of that climactic scene, we enter the boardroom knowing how the decision will play out. The work’s been done. Replay history 1,000 times starting from the initial flop of the 386 in 1988, and 900 times there’s never someone like Dennis Carter who goes to Denver. No one takes the founder’s stance. 90 times the “ignition team” fails to ignite the organization: they don’t figure out the problem fast enough, or they can’t effectively tell the story of what they’ve done, or they fail to build a broad enough coalition to nail the multi-city test and establish the case for a national campaign. Of the 10 times the campaign makes it to the boardroom, perhaps in half of those the edge of the message has been dulled—it’s feels risky enough to run a campaign at all, so the campaign itself plays safe. Something like the Red X only makes it to the boardroom one time in 200. Even if one played out this segment of history a thousand times, in none of these histories would Dennis Carter’s team bring something as bold as the Red X to the boardroom, only for Andy Grove to turn it down.

Dennis Carter’s story teaches a fundamental lesson about undertaking the impossible. The founder’s stance begins by leaving the safety of the job that’s been defined, and embracing larger mission, beyond one’s grasp: in Dennis’s case, the mission to create consumer demand. But this is simply the beginning. The real heart of the founder’s stance is the daily choice to leave the default path for an extraordinary path, on which we relentlessly confront the gap between the magnitude of the goal and the limits of our current reach.

On the default path, our picture of what the goal demands is fuzzy, and as a result we don’t experience much cognitive dissonance as we go about our days, doing what comes naturally and getting whatever outcomes follow from those steps. On the extraordinary path, our commitment to the goal is strong and sharp, and the gaps between the results we need and the results we’re getting stand out in vivid relief.

These gaps fuel the journey. These gaps compel the risks we take, and guide the hard hours spent preparing to navigate those risks well. These gaps send us beyond our familiar terrain, seeking new allies, passionately searching different fields for clues to the problems we know we can’t solve with the ingredients we have. These gaps guide us to practice the new skills that the mission requires that we master, even if we ourselves begin as novices.

Josh Waitzkin, famous as the subject of the book and movie Searching for Bobby Fischer, wrote about this kind of practice in his book The Art of Learning, which describes how he learned first to compete in chess at the highest levels, becoming an international grandmaster at 16, and then to master the martial art of T’ai chi ch’uan, in which he became the first westerner to win the world championship.

If a big strong guy comes into a martial arts studio and someone pushes him, he wants to resist and push the guy back to prove that he is a big strong guy. The problem is that he isn’t learning anything by doing this. In order to grow, he needs to give up his current mind-set…. [Josh’s martial arts teacher] William Chen calls this investment in loss….

I was wide open to the idea of getting tossed around—Push Hands class was humility training. Working with Chen’s advanced students, I was thrown all over the place. They were too fast for me, and their attacks felt like heat-seeking missiles. When I neutralized one foray, the next came from out of nowhere and I went flying. Chen watched these sessions and made subtle corrections. Every day, he taught me new Tai Chi principles and refined my body mechanics and technical understanding. I felt like a soft piece of clay being molded into shape. As the weeks and months passed by, I devoted myself to training and made rapid progress. Working with other beginners, I could quickly find and exploit the tension in their bodies and at times I was able to stay completely relaxed while their attacks slipped by me. While I learned with open pores—no ego in the way—it seemed that many other students were frozen into place, repeating their errors over and over, unable to improve because of a fear of releasing old habits. When Chen made suggestions, they would explain their thinking in an attempt to justify themselves. They were locked up by the need to be correct.

Dennis, too, must have felt like “a soft piece of clay being molded into shape” as he let Denver teach him and his team how to talk to consumers, how to understand the consumer’s needs, how to convey 32-bitness—and ultimately, how to rewire the logic of their industry.

This critical distinction between the default path and the extraordinary path can be summarized simply.

Steering by the extraordinary path doesn’t guarantee extraordinary achievement, but it opens the potential to transcend the limits we start with.

Undertaking the impossible reshapes us, if we let it. As we are reshaped, our possibilities widen. The vise that holds us loosens its grip. Time slows down; the blows that came at us with dizzying pace and unstoppable force can now be parried.

Through our odysseys, we become instruments of what we seek: instruments sharpened by the rigors of our work, polished by clarity of intent; instruments cutting away false assumptions, until all that remains is the action we must take, the choice we must affirm.

* Stephen Mitchell translation, Homer’s Odyssey, Book V

** This section draws heavily on Chapter 3 in Sally Helgesen’s wonderful 1995 book The Web of Inclusion. The reader is encouraged to read that chapter, “Marketing is Everything: Intel Corporation,” which explores the full arc of how Intel Inside came to be. This interpretation of the Dennis Carter story is mine; the underlying narrative of what happened comes almost entirely from Sally’s book.

Photo by Sean Benesh on Unsplash