It is rare to achieve anything important without sustained focus.

There are two possible paths to this focus. We might call one the path of resolution; the other, the path of receptivity. The path of resolution begins the long march before fully knowing the way. The path of receptivity wanders until the destination clicks. (Corporations have the same two paths. Henry Mintzberg wrote a seminal 488-page book about this, which he titled The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning.)

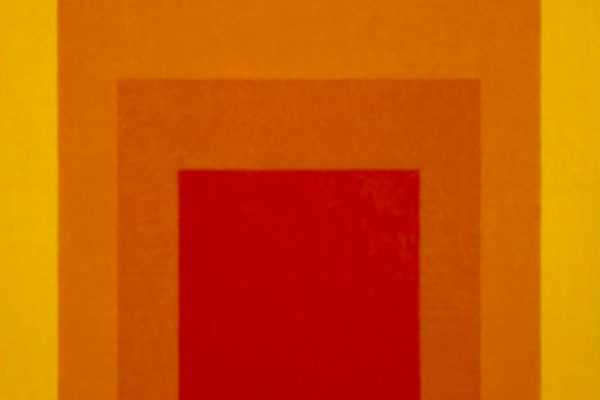

Really big goals require both paths at once, one nested inside the other: resolution on the journey, receptivity to the next path.

Recently, my friend Gustavo Alba sent me a sketch on two sides of lined paper that I’d made over breakfast at Balthazar, in the spring of 2013, trying to describe what I meant this new, still nameless firm to be. Part of this sketch was of what looked like layers of an onion: individual, group, unit, enterprise, coalition of actors. I’d described to Gustavo that at the very heart of the firm, underneath the various business models I meant to build, was an inquiry into human enterprise: how people achieve large purposes, individually and together. This question applies at all the different scales represented by the slices of the onion, and at every scale of time, from the sixty minutes of a meeting to enterprises meant to last many lifetimes.

A few months later, Graham Duncan, who generously let us work out of his East Rock Capital office during Incandescent’s first year, suggested a lunch for himself, Josh Waitzkin and me for us to coach one another on the things we each wanted to learn. That lunch clarified my resolution that an intellectual project as ambitious as the onion required the regular discipline of writing.

George Bernard Shaw famously wrote: “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”

Intellectual progress unfolds by a parallel logic. Smart, successful people are typically satisfied with their understanding. They assimilate what they encounter to what they think they know. Intellectual progress demands a dissatisfied mind.

The poet Kay Ryan captures this:

New Rooms

The mind must

set itself up

wherever it goes

and it would be

most convenient

to impose its

old rooms—just

tack them up

like an interior

tent. Oh but

the new holes

aren’t where

the windows

went.

On Human Enterprise has been a space for figuring out how to put the windows where the holes are, as we encounter various challenges in the course of practical work advising and building businesses, and practical work trying to effect changes for better in the world.

The practitioner’s maxim is to solve a problem at the lowest level that works. The theorist aims to make an explanation cover the broadest possible class.

Neither approach, unmixed, advances our understanding of the onion much. The practitioner’s answers don’t have much reach. Her answer to the case at hand leaves most of what we know unchanged. The theorist is rarely dissatisfied. It’s easy for him to regard his understanding as sufficient, when his eyes aren’t pried open by the humbling experience of regularly falling short of practical goals.

These 114 posts often begin from some small kernel that has our attention, grains of sand on the beach of a theory of management.

- Top management at one of our clients keeps talking being the “most customer centric X company.” Is that a strategy?

- We’ve seen a number of ventures articulate a desire to go from having a single leadership team to having two groups: a small one that drives decision-making and a larger one that gives a range of senior people a voice. When does this make sense to do?

- It proved incredibly valuable to us at Katzenbach Partners to create an environment in which people could talk openly about pursuing opportunities outside the firm. Could something we called the retention tree, which was at the heart of how we achieved this openness, work for others?

Other posts hazard to grasp big questions from the top down. What counts as strategic clarity? What is the work of the team at the top of an enterprise? How does one hire well?

I hope to make the reader feel drawn into the circle of one of those conversations that isn’t meant to end, where each question seems to open up a new vista. Adam Grant stops by and asks how can a culture deliver both cohesiveness and divergent thinking. Someone asks what to do about having a great job working for the wrong boss, and everything stops for long enough for that question truly to get its due. We’re talking about something, but in the midst of that we’re talking about life: births and deaths, the torrent of events around us, the dailiness that when it runs over us is “well water pumped from an old well at the bottom of the world.”*

This post marks the relaunch of On Human Enterprise. We’ve rebuilt the site to make it easier to find posts that meant something to you, and to find others that someday might.

Our underlying journey will continue as it has been from the beginning. This is simply a moment to pause, to recall where we’ve been going and why, and then to put one foot in front of the other: resolved on the journey, receptive to what might unfold just beyond what yesterday’s eyes knew how to see.

* Randall Jarrell, “Well Water”