Two weeks ago, I wrote a piece looking back at nine moments in Incandescent’s first decade that represented early turning points of learning and growth. Here I’d like to try something harder: to express the past decade as an extension of one conversation.

I spend most of my waking hours in conversation, often talking with people about what they are experiencing as most consequential and most difficult in their work.

The spirit of this piece is to bring you into conversation with me.

I mean to say:

Come and talk.

May I share with you one moment that mattered to me?

May I show you how that moment contains everything I am coming to know?

Lunch with Graham and Josh

After I left Bridgewater, Graham Duncan, co-founder of East Rock Capital, invited me to work out of their offices on 53rd Street. A rent-free office during the period when I was first bootstrapping what would become Incandescent was generous; the opportunity to hang out with Graham and be in the flow of people and ideas that always swirls around him was irresistible.

One day, Graham suggested that he, Josh Waitzkin and I have a mutual coaching conversation over a long lunch down the street at The Modern. While East Rock’s business is a fund of funds that serves as a generational wealth manager for a small number of families, what Graham really does is seek out, evaluate, and nurture talent. One of Graham’s mantras is that “talent is the best asset class,” an idea he expands on beautifully in his podcast with Tim Ferriss. Josh Waitzkin grew up as one of the best young chess players of his generation – he’s the protagonist of Searching for Bobby Fisher. After stepping away from competitive chess at 22, took up Tai Chi Push Hands, and became a world champion in the sport. His book, The Art of Learning, shares the method of learning by which Josh learned to master these different disciplines. Being invited to a mutual coaching session with these two felt like if John Coltrane rang up to tell me that he and Charles Mingus were going to spend an evening jamming, and ask whether I would like to join in?

Graham was enough of a regular at The Modern at the time that he had an arrangement that when his team made a reservation, they’d share exactly how much time Graham had, and the staff would orchestrate the meal to fit that container This particular meal had no time boundary; we’d follow the conversation wherever it was meant to lead.

What Graham’s and Josh’s coaching helped me see was:

- I’d gone back to consulting because I loved doing my work in conversation: both the real-time exchange of ideas and the way that writing down my thoughts for clients created the opportunity for a slower, more extended form of dialogue. Those were practices to deepen every day.

- And, at the same time, my work would become more meaningful if I invited myself to operate on a higher plane. Whatever was in focus in my daily work could become an opportunity to think about the “general case,” of which the particular case at hand was simply an expression.

- Just as our clients hired us to help them achieve some important and difficult goal, we needed to hire our clients to help Incandescent make discoveries and sharpen our craft. Josh needed both competition and practice to become the best in his field; I needed to find the right mix of live work and reflective practice in order to keep progressing at a career stage when many people plateau. Business people often spend almost all their time in “competition” and almost none in practice. I would need to make radically different choices.

- The medium to do this larger work was in writing. In my prior chapter as a founder, building Katzenbach Partners, I’d never given myself much space to write, because that had never felt as important to my goals as the work of entrepreneurial leadership, rainmaking and advising clients. I needed to change that, and to recognize that writing would be my vehicle for reaching toward greater mastery of a larger game. Writing wasn’t in service of building an audience or building a business. Writing as a learning practice was an end in itself.

One of the immediate outcomes of this coaching session was to begin writing what became this blog, On Human Enterprise. It’s hard to imagine a day since that couldn’t be understood more richly and more deeply by placing whatever I was doing or thinking as in conversation with myself at the moment of that lunch, gaining a clearer understanding of what my real work is.

Josh’s Voice

From The Art of Learning, pages 53 - 54:

In performance training, first we learn to flow with whatever comes. Then we learn to use whatever comes to our advantage. Finally, we learn to be completely self-sufficient and create our own earthquakes, so our mental process feeds itself explosive inspirations without the need for outside stimulus.

The initial step along this path is to attain what sports psychologists call The Soft Zone. Envision the Zone as your performance state.

You are concentrated on the task at hand, whether it be a piece of music, a legal brief, a financial document, driving a car, anything. Then something happens. Maybe your spouse comes home, your baby wakes up and starts screaming, your boss calls you with an unreasonable demand, a truck has a blowout in front of you. The nature of your state of concentration will determine the first phase of your reaction – if you are tense, with your fingers jammed in your ears and your whole body straining to fight off distraction, then you are in a Hard Zone that demands a cooperative world for you to function. Like a dry twig, you are brittle, ready to snap under pressure. The alternative is for you to be quietly, intensely focused, apparently relaxed with a serene look on your face, but inside all the mental juices are churning. You flow with whatever comes, integrating every ripple of life into your creative moment. This Soft Zone is resilient, like a flexible blade of grass that can move with and survive hurricane-force winds.

Finding my work wherever I am

In my thirties, one of my struggles was how to find my way onto big enough stages, to be able to do work that was large enough and challenging enough to stretch me and drive my learning. I’d imagine this is very much like Josh in chess or in martial arts needing opponents who were strong enough to challenge him, or even strong enough to over-master him until he learned something fundamentally new. From The Art of Learning (page 110):

I spent many months getting smashed around by Evan, and admittedly it was not easy to invest in loss when I was being pummeled against walls – literally, the plaster was falling off in the corner of the school into which Evan invited me every night. I’d limp home from practice, bruised and wondering what had happened to my peaceful meditative haven. But then a curious thing began to happen. First, as I gotit got used to taking shots from Evan, I stopped fearing the impact. My body built up resistance to getting smashed, learned how to absorb blows, and I knew I could take what he had to offer. Then as I became more relaxed under fire, Evan seemed to slow down in my mind. I noticed myself sensing his attack before it began. I learned how to read his intention, and be out of the way before he pulled the trigger. As I got better and better at neutralizing his attacks, I began to notice and exploit weaknesses in his game, and sometimes I found myself peacefully watching his hands come toward me in slow motion.

Part of the challenge of consulting is that in order to work on a hard enough problem, the leader who owns that problem needs to see the value of sharing that problem deeply with me. The cost of our work is almost a secondary consideration. The harder leap in the consulting “sale” – a leap that isn’t anywhere near finished when a contract is signed – is the leap truly to engage in co-discovery and co-creation. Part of what motivated me in the sale of Katzenbach Partners to Booz & Company was the belief that by being part of a larger firm with a much wider and deeper set of capabilities, I would enter a competitive field where I could learn from solving larger and harder problems.

By the time of the lunch with Graham and Josh, I had begun to see that while, of course, it was true that finding the right problems to solve with the right people would accelerate my learning, the opposite truth was more important. I needed to become less dependent on being in the “right” place. I needed to enter a deeper Soft Zone in which the work that mattered – the general case of how people can accomplish what’s essential and difficult – could be found wherever I was.

Graham’s Voice

Graham begins the best essay that I’ve ever read about the art of hiring:

The philosopher Kwame Appiah writes that “in life, the challenge is not so much to figure out how best to play the game; the challenge is to figure out what game you’re playing.”

When I try to figure out what game I’m playing, I see that for the last 25 years I have been playing a game of strategy applied to people, a game where over and over I try to answer the question “what’s going on here, with this human?”

When I look back at the last ten years, the game I’m playing is this:

Each of the people and organizations I care about working with are on an odyssey:

They’re trying to get somewhere out of reach.

Where are they truly seeking to get? How do they advance closer? Whom do they need to become in order to make the journey, and what will it take for them for them to change

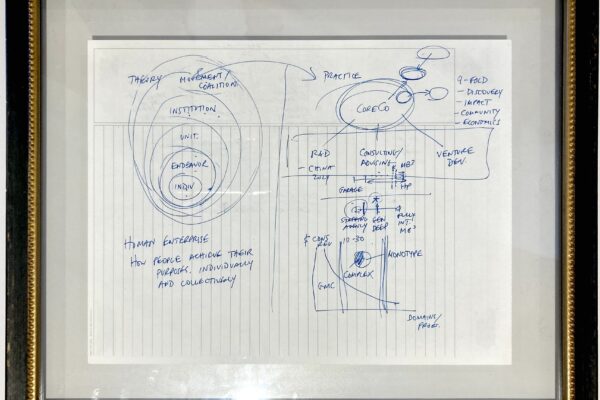

And, as each situation shows me a facet of some larger whole, what am I learning about the shape and nature of an odyssey? How can I map the terrain of how we achieve something greater than ourselves, across each of a nested set of levels: individuals, groups, organizations, constellations of organizations?

Later in his piece, Graham quotes the poet David Whyte on how lives and careers unfold “in conversation with reality”:

Whatever a human being desires for themselves will not come about exactly as they first imagined it or first laid it out in their minds…what always happens is the meeting between what you desire from your world and what the world desires of you. It’s this frontier where you overhear yourself and you overhear the world.

And that frontier is the only place where things are real…in which you just try to keep an integrity and groundedness while keeping your eyes and your voice dedicated toward the horizon that you’re going to, or the horizon in another person you’re meeting.

The game I’m playing can only be played in conversation with reality, and in conversation with what matters most in the realities of others.

At lunch with Graham and Josh, part of what clicked into place was that I needed to be able to pick up this conversation anywhere – paraphrasing Rumi, to see the ocean in every drop.

Beginning On Human Enterprise

As I began writing this blog, I sought to create a vehicle to practice looking anywhere, picking up my particular conversation with reality, and rendering my way of seeing the world so it could be seen by others. After a first post introducing the blog, my next post was called “Macro-Miniatures.”

How can we see the way large forces shape the world? Social sciences give us frameworks and patterns to understand forces in their separate functions…. Often, though, what we want in understanding the world is more than this. We don’t just want to understand the weather patterns that shape a temperate climate and the botany of coniferous trees. We want to look at the forest and understand the many interacting layers that make it work the way it does, the way we see it unfolding as we come to know it through the seasons. Macro-miniatures meet this need. They plumb a specific context to show what shapes it and transforms it over time.

David Liittschwager’s wrote a beautiful book called A World in One Cubic Foot, for which he carriedbrought a one foot cube around the world, and, in each place he visited, photographed all the life moving through that cube over twenty-four hours.

My work, I was realizing, was to look anywhere, and perceive all the dynamics flowing through that specific there.

Hake 1 Plastics Avenue in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, near where I was born: the SABIC Innovative Plastics Plant. The plant was originally built by GE in 1903. Through this “one cubic foot” one sees:

• The rise of plastics and the mass application of materials science in the postwar period, and the way these innovations intertwined with events in history (GE’s Lexanwas used in the bubble helmets of the lunar astronauts

• The changing nature of the global conglomerate – Jack Welch began his GE career in Pittsfield as a chemical engineer in 1960, and was almost fired in 1963 for an explosion that blew off the roof of a pilot plant

• The shifting currents of energy markets, as booms and busts in petrochemicals changed the economics of the plastics business

• How the economics and politics of energy led to the creation of SABIC (Saudi Basic Industries Corporation), formed in 1976 and now among the world’s 100 largest corporations, which purchased GE’s Plastics unit in 2007

The particular nature of each big force stands out most clearly through the distance of abstraction. The world that is the product of many forces must be understood through the forests of particular realities, the macro-miniatures that show us the grain of how things work.

Graham’s Voice

Almost ten years after our lunch with Josh, I’m sitting in a coffee shop reading Graham’s words:

Lately, I’ve been thinking that if I have one particular skill, it is finding great partners and building trust with them.

I love discovering the topics and areas to which each person I meet brings unusually high credibility, and constructing systems that have as many people as possible doing what they love to do. When it works, those systems are less fragile, anti-fragile even, because of the way everyone is operating in their zone of genius—that area beyond their zone of competence and even their zone of excellence, the thing they most love to do.

For me, there is no end to this activity, no prize or summit where I’m done and will feel satiated. To build trust is enjoyable in its own right.

It’s what the philosopher James Carse calls an “infinite game.” A couple of years ago I had the chance to ask Carse how he had come up with the idea of an infinite game. He told me a story about watching his kids play.

Sometimes, their goal was to end the game—to win, to get that trophy. Carse called that a finite game.

Other times, their goal was not to win, but to play the game as long as possible and to recruit others to join in—an infinite game.

As Carse sees it, the rules of a finite game are unique and fixed. If the rules change, a different game is being played. Think poker. If you change the value of the hands, you’re no longer playing poker, you’re playing something else.

The rules of an infinite game, in contrast, can change in the course of play. While finite games are, in Carse’s explanation, like a boundary—you can approach and step across, infinite games are like a horizon—as you move toward it, the horizon keeps moving away from you. Finite players play within boundaries; infinite players play with the boundaries themselves.

Every encounter with someone – in life or on the page – who is playing an infinite game feels both like a meeting of the minds and an occasion for me to become an apprentice.

This Infinite Game

In his book The Five Invitations: Discovering What Death Can Teach Us About Living Fully, Frank Ostaseski, co-founder of the Zen Hospice Project, describes one moment in his work:

Samantha was a wilderness guide in her mid-forties. I sat with her one endless night as her husband, Jeff, was dying. She asked me what she could do for him that might help.

I asked, “What do you do when your young children are sick?”

She said, “Well, I sit quietly right next to their bed, or sometimes I snuggle up with them. I speak less and listen more. I let them know I am right here with them. I retell them in words and in touch how much I love them.”

“Beautiful,” I said. “What else?”

I could see her remembering what she already knew.

She almost whispered, “I try to create a kind environment that is peaceful so they are not as afraid. I try to do simple things with great attention. I promise I won’t leave them. I tell them it’s okay that they are sick and that it won’t be like this forever.”

There is always some way to be what the moment asks of us. This is the infinite game, to be with each moment as though we will always be in conversation with this now.

In the next decade of this finite life and infinite endeavor, I wish: to remember more fully what I deeply know; to converse with reality, joyfully and tearfully; to ask reality to teach me, and to quarrel with it; to make the sped-up world slow down; to see in each luminous conversation the way it can illuminate the balance of a life.