In our work with leaders in large companies, a central tension we’ve seen is finding the right balance of independence from, and connection to, the broader enterprise. Innovation efforts need to cultivate the right independence, so that the gravitational pull of “business as usual” won’t draw them back into the commonplace. But if innovation efforts aren’t sufficiently linked to the broader organization, they likely won’t scale and almost certainly won’t have a transformational effect.

There are some structural approaches that can help. Vijay Govindarajan and Chris Trimble’s model of a “distinct and linked” architecture is one. First posed in their Ten Rules for Strategic Innovators, this model proposes that the new business exist as distinct from the core, yet linked in a couple high-leverage areas, with senior executives helping to keep these links healthy and productive. In this way the new business can avoid the traps that come with being entirely distinct from the core and isolated from it, while also avoiding the traps of being too closely integrated.

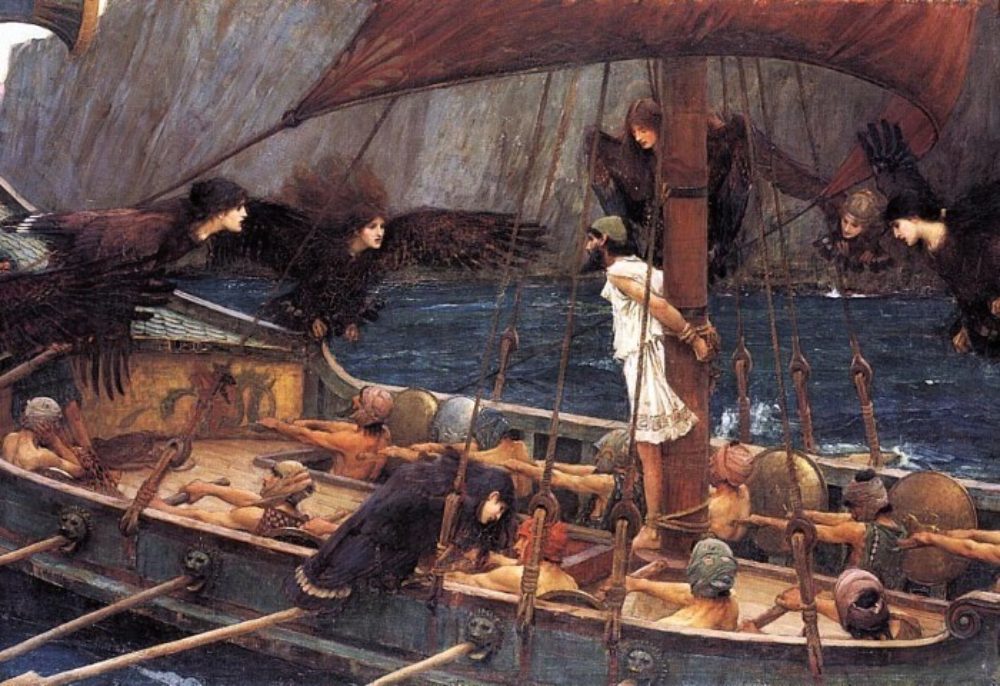

But while certain critical structural decisions such as “distinct and linked” can be made up front, many of the factors critical to putting innovation on a breakthrough path will evolve as the innovation journey progresses. In Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey, the hero Odysseus anticipates the dangers of the sirens, whose enchanting singing lures sailors to shipwreck off the coast of their island. Odysseus orders his men to plug their own ears with beeswax and to tie him to the ship’s mast, ears unplugged, but not take him down until they pass the island, no matter how much he begs. Like Odysseus, we can anticipate with clarity that initiatives chartered to aim for a transformational goal will encounter siren songs, luring leaders who set out in search of innovation back toward the shallows of business as usual. We all know these siren songs:

- Focus on what we can announce soon, putting the theater of forward movement above the slow march to transformational impact

- Prioritization on goals the core business already has, versus even when impact is small and incremental, opening the horizon of new goals

- Pressure to show that work is on track, shifting goal posts if needed, rather than holding up a mirror to confront a trajectory that’s falling short of the original vision

- Defaulting to work with the resources at hand rather than figuring out who could contribute to a breakthrough and going in pursuit of that talent

- Avoidance of conflict, even as innovation efforts that cut against an organization’s grain suffer “death by a thousand blows” – or dismissing conflicts that arise at a working level as squabbling, rather than addressing the underlying sources of conflict

It’s easy to resolve as we’re in port and as we set sail, full of optimism, that this voyage will resist these siren songs. Tired, far from home and short of provisions, the siren songs become tremendously difficult to resist.

A common approach to managing the unpredictability inherent in such innovation voyages is to create a set of metrics and milestones that ensure there’s visibility at the very top of the organization about whether the initiative is moving forward. While completion measures for early milestones create a feeling of discipline and focus, they can mask the larger danger that the actions identified don’t in fact put the organization on a path to achieve the transformational goal that motivated the initiative in the first place. This danger is especially great if siren songs bend the milestones measured away from the big goal and toward other priorities closer to hand.

It is useful to distinguish between two kinds of risk:

- Completion Risk: identified action steps are not completed within the articulated parameters for success

- Entrepreneurial Risk: identified steps are completed, but nevertheless the “venture” fails to achieve its core long-term goals

Often, reporting on innovation initiatives at the enterprise level focuses on managing completion risk – but for initiatives that aim for a breakthrough, entrepreneurial risk is the far more important risk to manage.

Managing entrepreneurial risk is hard. While there doesn’t exist a set of process steps that can program this difficulty away, certain disciplines do make a difference. Particularly important is to create a forum for stepping back on key innovation journeys, reconnecting with the big goals that animate the journey, and getting above the day-to-day push toward specific intermediate milestones to evaluate the trajectory toward the big goal.

A critical part of doing this well is creating a supportive environment for leaders to synthesize the trajectory as “red” and confront key gaps and issues, without devolving into blame or feeling they already need to know how they will remedy the gap. The nature of entrepreneurial risk is that if the goal is big enough and the territory uncertain enough, the trajectory will become red at multiple points in the journey. Both the teams owning the work and their executive sponsors will find themselves stuck. The impulses to quit, to shrink down the goal to something more tractable, to pivot to some new (and generally equally unproven) path, and simply to grit one’s teeth and redouble one’s efforts are all natural at these junctures. There’s no algorithm that reliably guides which of these impulses to attend to and which to suppress.

Steering through these junctures is the hard work that tests the mettle of both entrepreneurial owners of innovation efforts and executive sponsors. While organizational architecture and the design of innovation process can’t eliminate the need for this work, careful design can create time and space to do this work well.